Gone with the wind

Conservation of the “War atlas” from the Military History and Culture Center (Barcelona)

I don’t like much having war books, but I must admit that this one is particularly beautiful. The velvet binding seemed to me a challenging issue on the restoration, which did not have major complications besides this.

I show the restoration of this book because of the headaches it has given me when solving the lost areas, the wooden work. The considerable losses on a laborious woodcarving work, and the lack of originals of many of the missing pieces fairly complicated the subject (the shields on the corners were different).

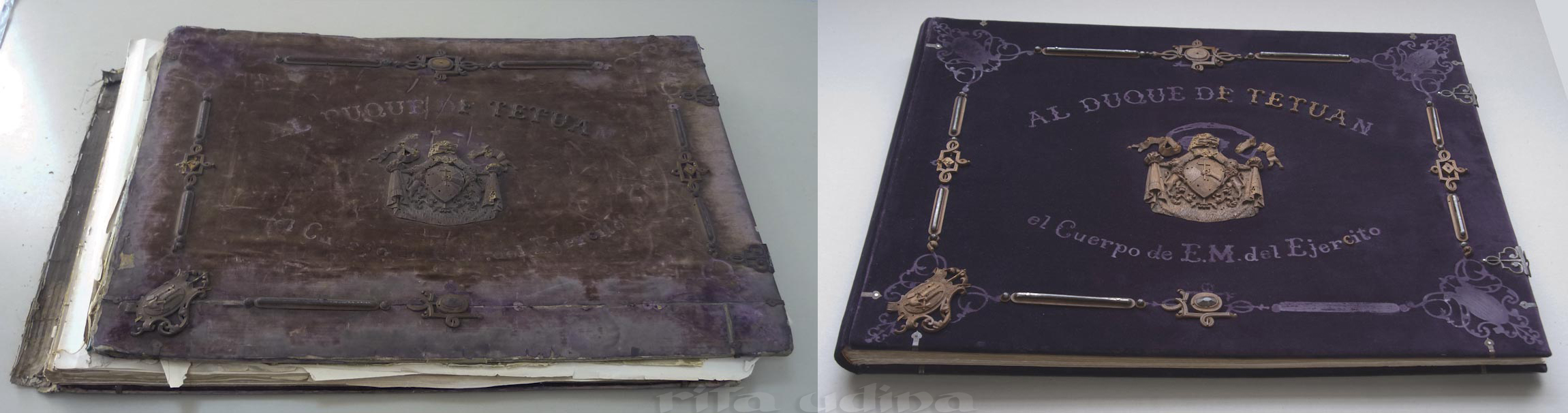

The book before (top left corner) and after the restoration (right bottom corner). Photomontage of the two original images.

Description of the book:

The “Historical and topographical atlas of the african war, sustained by the spanish nation against the morrocan empire between 1859 and 1860” is an oversized book (52 x 70 x 4,5 cm) with contemporany binding. The velvet-lined covers had wood and metal decoration. The endleafs and the hinge were made of watered silk, and it had gilt edges. Despite the glow that it must have had, some details escape from absolute delicacy, such as headbands, which were machine-made type, and also the metal inlays, made of clumsy iron (though very appropriate to the war theme… would they be from grapeshot?). But the refinement of the wood carving is truly remarkable and so was the quality of velvet, of the moiré silk and the gilding, as well as the content of the book. It contains fantastic lithographic prints on two inks, and unfoldable maps watercoloured by hand.

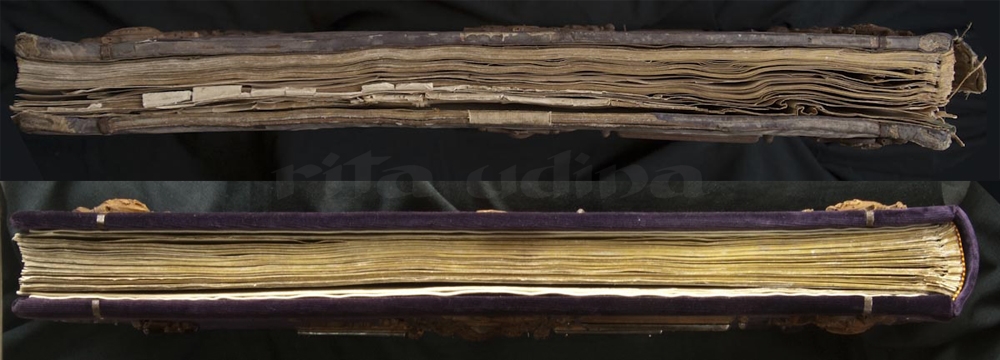

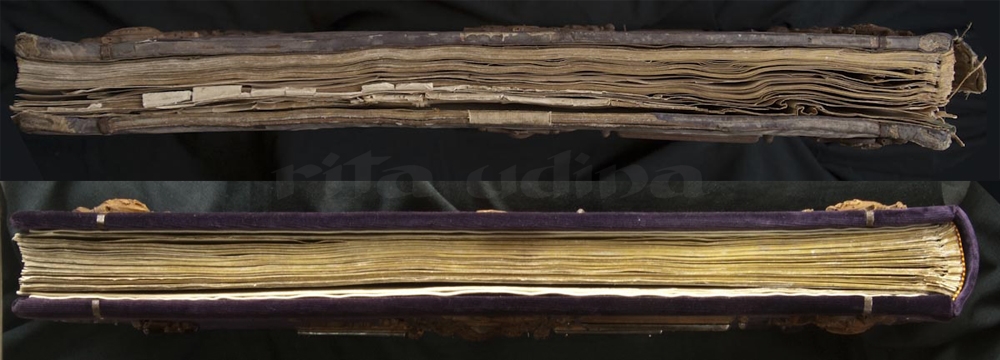

Its spine is straight, with flexible recessed cord-sewing and concertina guards, in which the folded maps and plans were mounted.

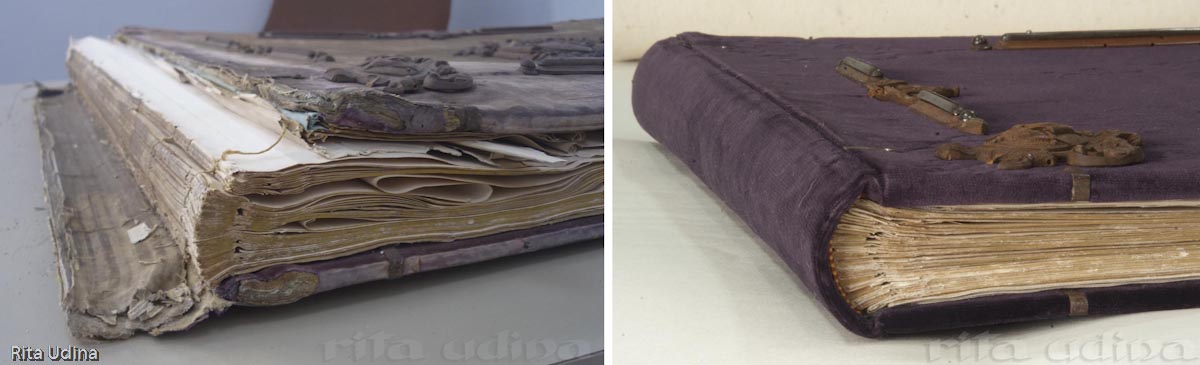

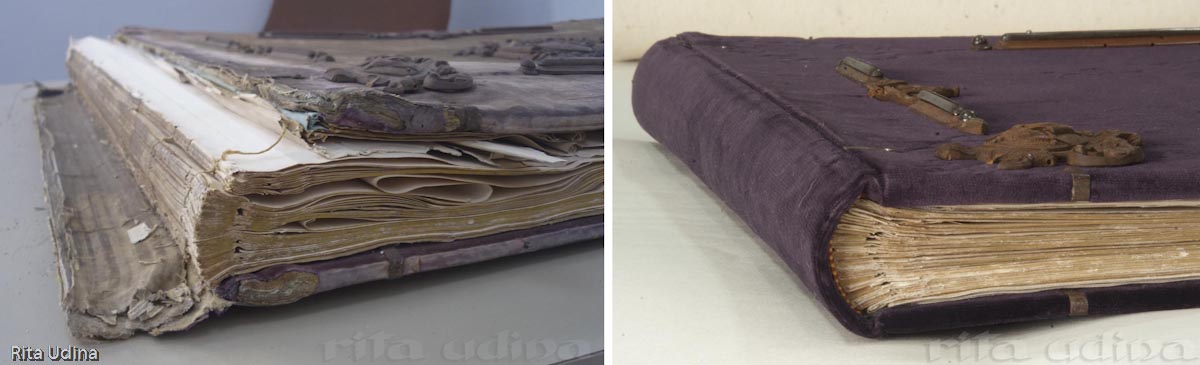

Left: Before restoration. Detail of the gilt tail edge. The straight spine with recessed-cord sewing. The front cover and spine are loose, and the tail headband is lost.

Right: After restoration. The velvet has been replaced, keeping the original decorative elements. The lost headband has been reestablished by a similar one to the fore-edge.

Damages:

- The front cover was loose, and the spine was only joint together by the back cover. The wooden inlays were heavily eaten away by woodworm, and there were considerable losses: many of the pieces were missing (almost all the letters on the front cover).

- The metal parts of these decorations were deeply rusted.

- The velvet was very worn and faded, specially on the front cover.

- The moiré silk endleafs were very dirty, with damp stains. They were brittle due to a non adequate glue added in the past.

- The paper sheets had tears and ripped edges, with damp stains and also mould discolouration. Some of the sheets were unstitched and the areas affected by mould really brittle.

- The protection onion skin paper sheets which precede the engravings were deeply oxidized and quite crumpled.

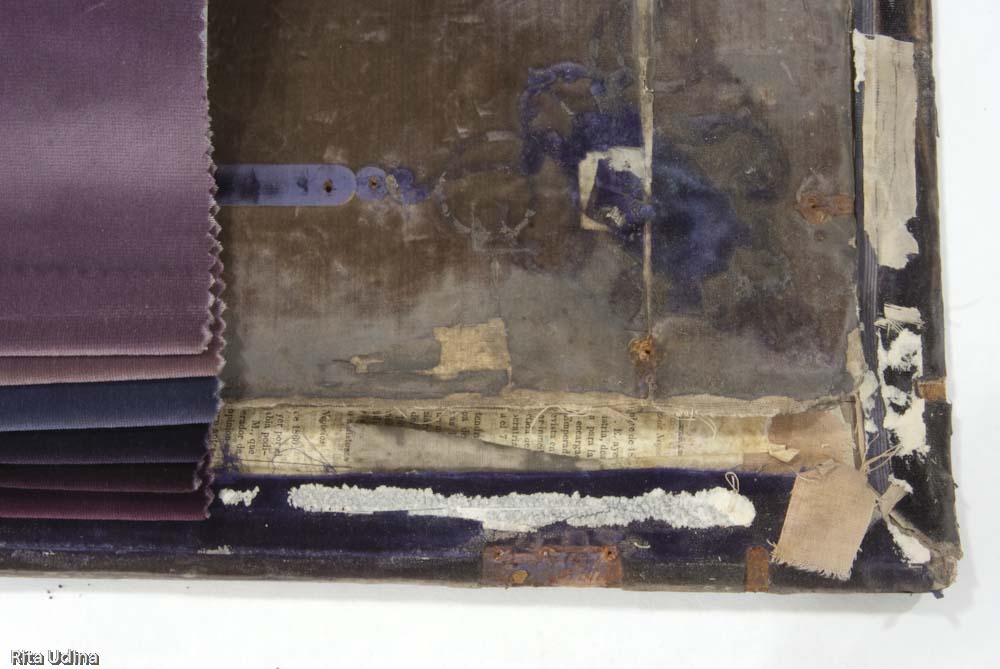

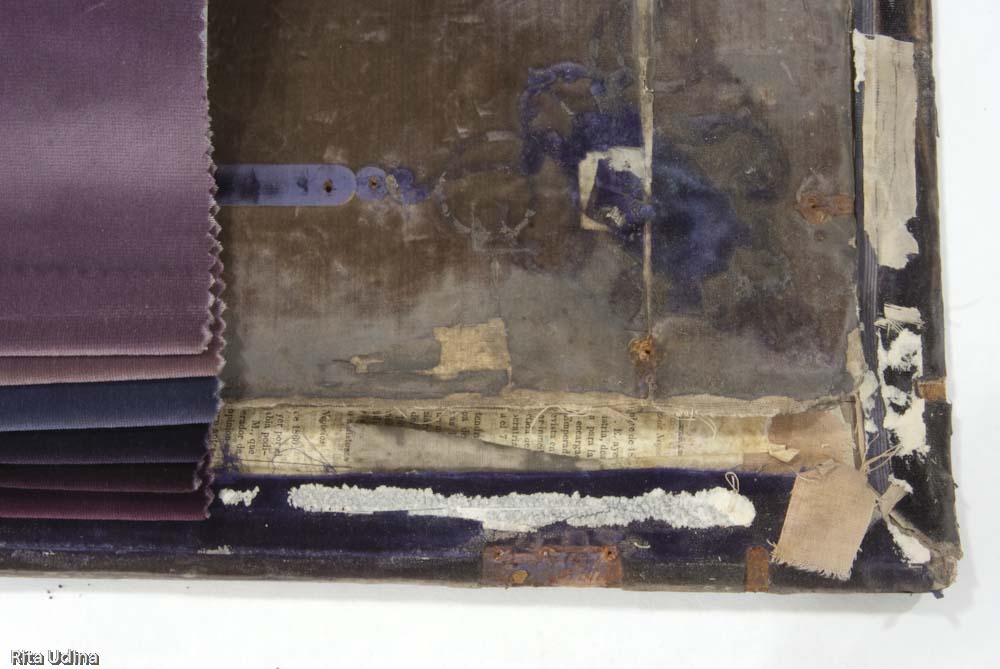

Restoration process. Front cover after removing the decorative inlays. Deepness of the original purple colour is now clearly appreaciable, as well as the effect of light on the rest.

Restoration process:

Revision of pagination and unbinding of the book.

Treatment of the paper sheets:

– Disinfection, water cleaning

and aqueous deacidification (with calcium hydorxide).

– Consolidation: sizing and reinforcement of tears and brittle areas. Flattening.

Treatment of the binding:

- Disassembling the covers required to take away the wood and iron inlays. All of them were numered to be able to put them back in their original position. While removing these pieces the original colour appears clearly again: deep purple, that had become worn-out brown by the effect of light.

Locks from the front cover, before (top left corner) and after removing the rust and applying a protection varnish (right bottom corner). Photomontage of the two original images.

- Treatment of the inlays: Removal of rust and applying a protector varnish on the iron pieces. Cleaning and disinsection of the wooden ones. The broken iron clips that fixed both wood and cover boards have been repaired with welding lead.

- Sewn: The original recessed-cord sewing is reproduced with new cords. New bicolour headbands are added, similar to the fore-edge remaining one.

Binding:

– Non-faded areas are taken as a reference on the search for a new velvet to replace the old one.

- Binding with the chosen new velvet, adding the restored inlays on its original positions.

Velvet samples from which the third from the bottom is chosen, on the search for the major resemblance with non faded areas.

- New watered silk endleafs and hinges are put, pretty much similiar to the ones it had. The old attempts of consolidation with non flexible adhesives had exceedingly brittled the original silk, and the damp stains impoverished its aspect. Due to these facts I considered it worth to replace some original supports instead of restoring them.

Binding: A plastic template (1st image) that was previously made on the disassembling is used as a guide. New velvet and original decoration pieces are added simultaneously.

Reintegration of wood losses:

Now that I’m writing about it, it seems such a silly thing because of its simplicity… but then it satisifies me greatly if it really is so, because it implies that the observer can understand what he sees with no need to incurre on a false historical criteria.

The absence of the missing inlays is resolved reproducing the imprint they had left. This way the loss is still intuited or drawn while there’s no need to do a complete reproduction of them all. That would have been costly on resources and complex on criteria, due to the lack of referents for many of them (specially the shields).

Some sort of plastic molds were made in order to mark the imprint on the velvet cloth. Plastic is easy to cut but also stiff enough to press, but still it doesn’t get stuck to the textile. Afterwards we realised taht there was the possibility of laser cutting them from a vector image… next time!

Plastic punched pieces to mark the velvet. Only the stamp minds, so we spared the 3D woodworking effort… no big deal! The pressing side is more finely delineated, that’s why the good sides are friendly labeled.

In addition to the pressure on the velvet, a soft glue is added (hydroxypropyl cellulose) to avoid the imprint from ruffling. This is the way the broken inlays are “finished”: the presence of the missing ones is suggested with no need to invent anything that hadn’t really been there.

Digital retouching was resorted to make the molds of the non-complete pieces (none of the big ones was): all the gaps were reconstructed with simple symmetries. But the lost letters obliged to reproduce directly from the stamp they had left.

Conclusion:

Replacing original components of a restored object always involves the risk of making it unrecognizable. The technical complexity of any treatment seems to me very small compared to taking such decisions: Shall I put the crumbled and stained endleafs? Shall I change the velvet?

As I explained in the previous post, there has to be a balance between the cost of a treatment and the value of what is being treated. It seemed to me that such a luxurious object requested to bring back its lost elegance. Despite how it looked like, I guess the book was never bound to lay on a battlefield.

Top lock before (left) and after restoration (right). It is made from iron and it was very rusty. Besides, note the glittering of the gilt edges of the sheets… there’s of course a reason why noble metals are distinguished from the rest!

Bottom corner before (left) and after restoration (right). The textile endleaf was very damaged and had an earlier intervention with non-elastic glue which stained and brittled the silk. Exceeding consolidation of supports that should be kept flexible (like silk) is a serious prejudice because they become eventually more fragile.

Tail edge before (top) and after the restoration (below). Several sheets were unstitched and shriveled, there was dirt all over, covers deformation, velvet abrasion and the spine was broken. The gilt edges after the restoration are the original.

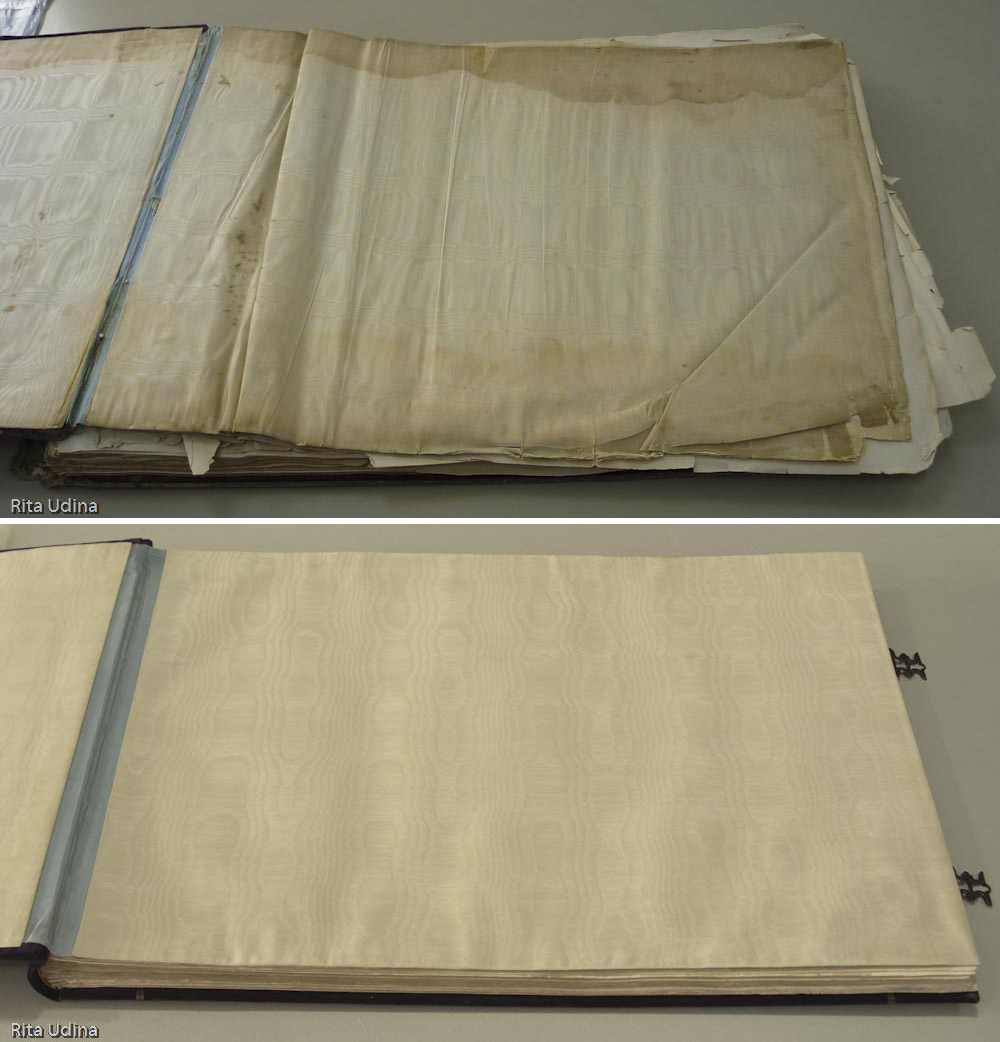

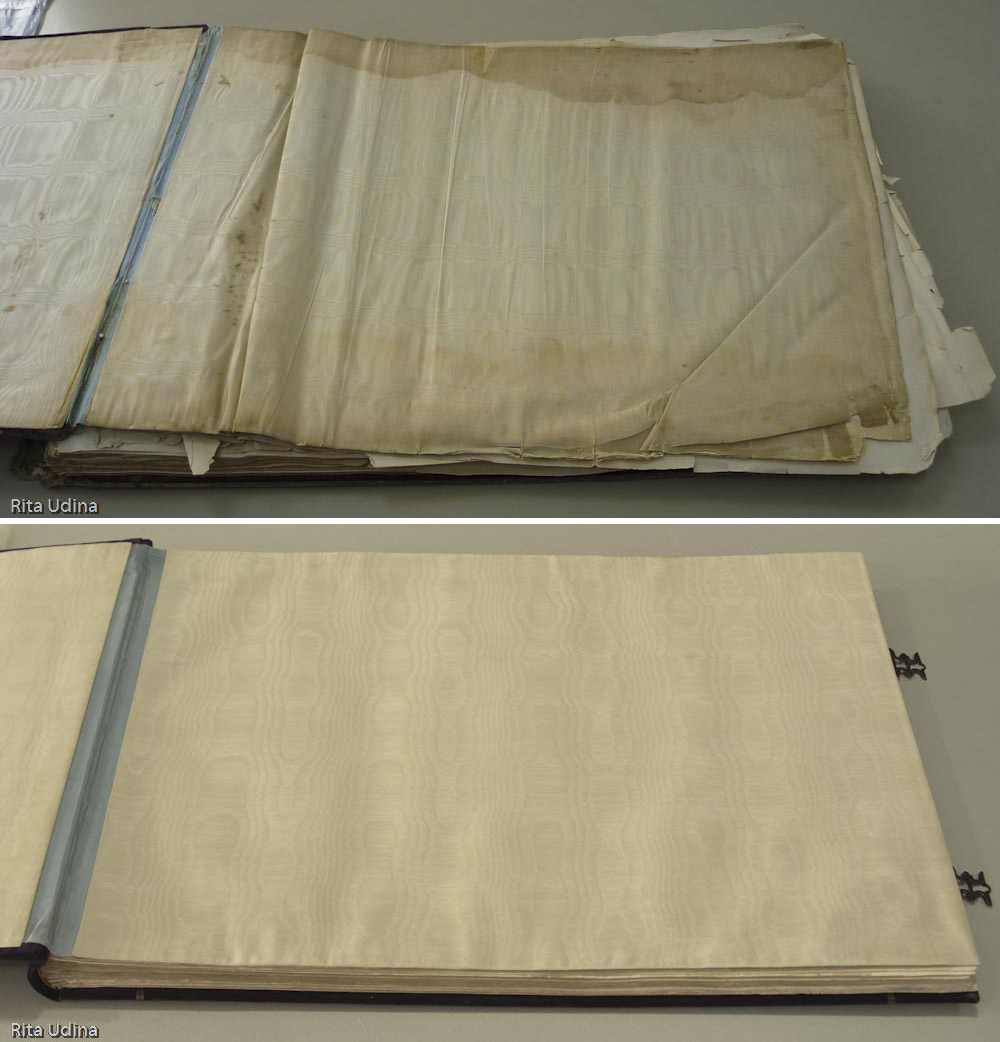

Front moiré silk flyleaf before (top) and after the restoration (below). It was all crumpled and had significant damp stains all along the fore edge, and so on the tail edge, though less. The pale blue hinge is also made of silk.

Related content:

Filter post by:

Gone with the wind

Conservation of the “War atlas” from the Military History and Culture Center (Barcelona)

I don’t like much having war books, but I must admit that this one is particularly beautiful. The velvet binding seemed to me a challenging issue on the restoration, which did not have major complications besides this.

I show the restoration of this book because of the headaches it has given me when solving the lost areas, the wooden work. The considerable losses on a laborious woodcarving work, and the lack of originals of many of the missing pieces fairly complicated the subject (the shields on the corners were different).

The book before (top left corner) and after the restoration (right bottom corner). Photomontage of the two original images.

Description of the book:

The “Historical and topographical atlas of the african war, sustained by the spanish nation against the morrocan empire between 1859 and 1860” is an oversized book (52 x 70 x 4,5 cm) with contemporany binding. The velvet-lined covers had wood and metal decoration. The endleafs and the hinge were made of watered silk, and it had gilt edges. Despite the glow that it must have had, some details escape from absolute delicacy, such as headbands, which were machine-made type, and also the metal inlays, made of clumsy iron (though very appropriate to the war theme… would they be from grapeshot?). But the refinement of the wood carving is truly remarkable and so was the quality of velvet, of the moiré silk and the gilding, as well as the content of the book. It contains fantastic lithographic prints on two inks, and unfoldable maps watercoloured by hand.

Its spine is straight, with flexible recessed cord-sewing and concertina guards, in which the folded maps and plans were mounted.

Left: Before restoration. Detail of the gilt tail edge. The straight spine with recessed-cord sewing. The front cover and spine are loose, and the tail headband is lost.

Right: After restoration. The velvet has been replaced, keeping the original decorative elements. The lost headband has been reestablished by a similar one to the fore-edge.

Damages:

- The front cover was loose, and the spine was only joint together by the back cover. The wooden inlays were heavily eaten away by woodworm, and there were considerable losses: many of the pieces were missing (almost all the letters on the front cover).

- The metal parts of these decorations were deeply rusted.

- The velvet was very worn and faded, specially on the front cover.

- The moiré silk endleafs were very dirty, with damp stains. They were brittle due to a non adequate glue added in the past.

- The paper sheets had tears and ripped edges, with damp stains and also mould discolouration. Some of the sheets were unstitched and the areas affected by mould really brittle.

- The protection onion skin paper sheets which precede the engravings were deeply oxidized and quite crumpled.

Restoration process. Front cover after removing the decorative inlays. Deepness of the original purple colour is now clearly appreaciable, as well as the effect of light on the rest.

Restoration process:

Revision of pagination and unbinding of the book.

Treatment of the paper sheets:

– Disinfection, water cleaning

and aqueous deacidification (with calcium hydorxide).

– Consolidation: sizing and reinforcement of tears and brittle areas. Flattening.

Treatment of the binding:

- Disassembling the covers required to take away the wood and iron inlays. All of them were numered to be able to put them back in their original position. While removing these pieces the original colour appears clearly again: deep purple, that had become worn-out brown by the effect of light.

Locks from the front cover, before (top left corner) and after removing the rust and applying a protection varnish (right bottom corner). Photomontage of the two original images.

- Treatment of the inlays: Removal of rust and applying a protector varnish on the iron pieces. Cleaning and disinsection of the wooden ones. The broken iron clips that fixed both wood and cover boards have been repaired with welding lead.

- Sewn: The original recessed-cord sewing is reproduced with new cords. New bicolour headbands are added, similar to the fore-edge remaining one.

Binding:

– Non-faded areas are taken as a reference on the search for a new velvet to replace the old one.

- Binding with the chosen new velvet, adding the restored inlays on its original positions.

Velvet samples from which the third from the bottom is chosen, on the search for the major resemblance with non faded areas.

- New watered silk endleafs and hinges are put, pretty much similiar to the ones it had. The old attempts of consolidation with non flexible adhesives had exceedingly brittled the original silk, and the damp stains impoverished its aspect. Due to these facts I considered it worth to replace some original supports instead of restoring them.

Binding: A plastic template (1st image) that was previously made on the disassembling is used as a guide. New velvet and original decoration pieces are added simultaneously.

Reintegration of wood losses:

Now that I’m writing about it, it seems such a silly thing because of its simplicity… but then it satisifies me greatly if it really is so, because it implies that the observer can understand what he sees with no need to incurre on a false historical criteria.

The absence of the missing inlays is resolved reproducing the imprint they had left. This way the loss is still intuited or drawn while there’s no need to do a complete reproduction of them all. That would have been costly on resources and complex on criteria, due to the lack of referents for many of them (specially the shields).

Some sort of plastic molds were made in order to mark the imprint on the velvet cloth. Plastic is easy to cut but also stiff enough to press, but still it doesn’t get stuck to the textile. Afterwards we realised taht there was the possibility of laser cutting them from a vector image… next time!

Plastic punched pieces to mark the velvet. Only the stamp minds, so we spared the 3D woodworking effort… no big deal! The pressing side is more finely delineated, that’s why the good sides are friendly labeled.

In addition to the pressure on the velvet, a soft glue is added (hydroxypropyl cellulose) to avoid the imprint from ruffling. This is the way the broken inlays are “finished”: the presence of the missing ones is suggested with no need to invent anything that hadn’t really been there.

Digital retouching was resorted to make the molds of the non-complete pieces (none of the big ones was): all the gaps were reconstructed with simple symmetries. But the lost letters obliged to reproduce directly from the stamp they had left.

Conclusion:

Replacing original components of a restored object always involves the risk of making it unrecognizable. The technical complexity of any treatment seems to me very small compared to taking such decisions: Shall I put the crumbled and stained endleafs? Shall I change the velvet?

As I explained in the previous post, there has to be a balance between the cost of a treatment and the value of what is being treated. It seemed to me that such a luxurious object requested to bring back its lost elegance. Despite how it looked like, I guess the book was never bound to lay on a battlefield.

Top lock before (left) and after restoration (right). It is made from iron and it was very rusty. Besides, note the glittering of the gilt edges of the sheets… there’s of course a reason why noble metals are distinguished from the rest!

Bottom corner before (left) and after restoration (right). The textile endleaf was very damaged and had an earlier intervention with non-elastic glue which stained and brittled the silk. Exceeding consolidation of supports that should be kept flexible (like silk) is a serious prejudice because they become eventually more fragile.

Tail edge before (top) and after the restoration (below). Several sheets were unstitched and shriveled, there was dirt all over, covers deformation, velvet abrasion and the spine was broken. The gilt edges after the restoration are the original.

Front moiré silk flyleaf before (top) and after the restoration (below). It was all crumpled and had significant damp stains all along the fore edge, and so on the tail edge, though less. The pale blue hinge is also made of silk.