Endbands, headbands and ties

Endbands structural classification, and stuck-on endbands conservation

I have always thought that the endband to a book is like the tie to a suit. They both give their owner the chance to stand out, bearing a stylistic freedom that only a complement can have. The same as with ties, the aesthetical function of headbands has transcended the eminently practical.

Headbands had in origin the goal to keep the bookblock compactness along the head and tail of the spine; they were actually meant to bear the main joining to the boards. Nowadays headbands are generally “useless”, non functional [1]. This part of the book rarely foregrounds the untrained eye, but it depicts a true hallmark to the expert book-lover. It is like the icing on the cake, and gathers the bookbinder’s proficiency and taste. We might find discrete headbands, sophisticated, sloppy, with tabs, elegant, sporty…

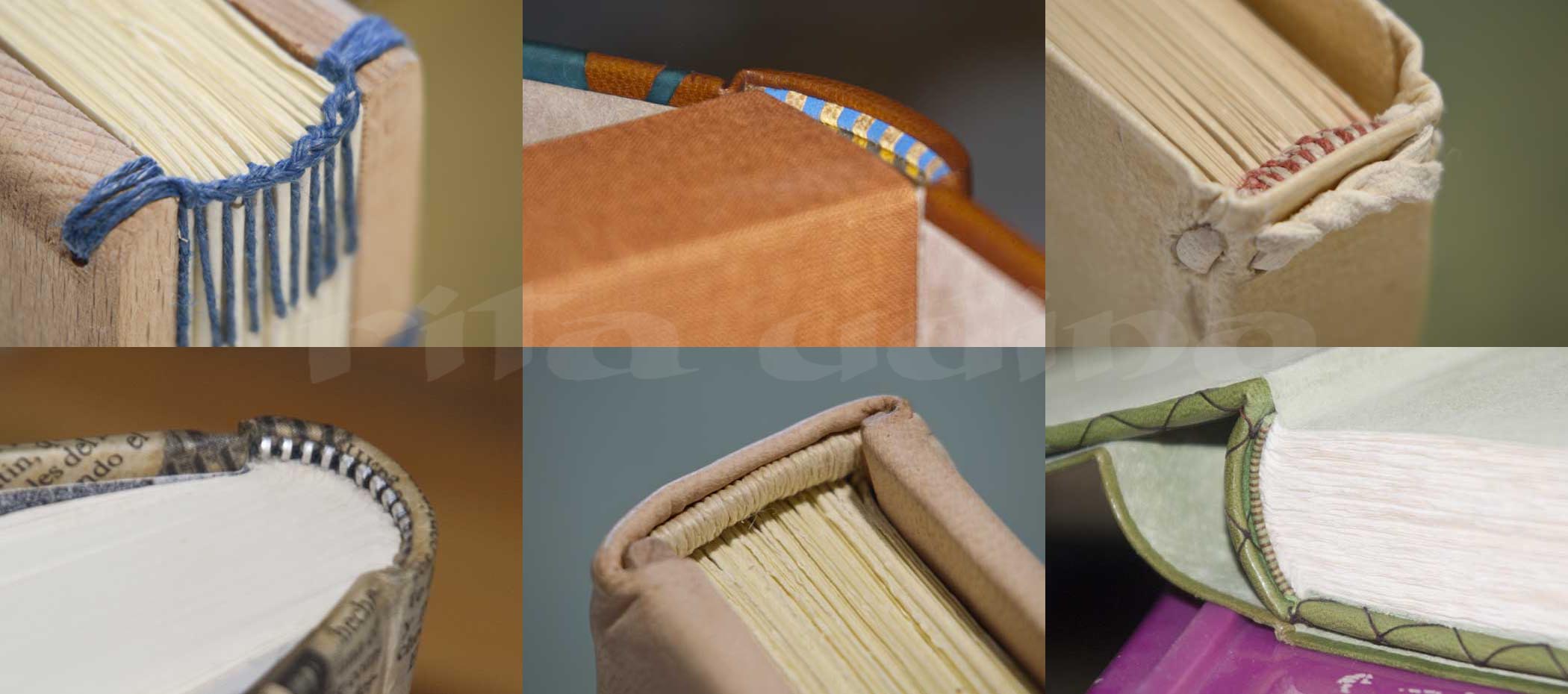

From left to right, and from top to bottom: 1. Sewn braided headband without core. Coptic wooden-boarded bookbinding model.[2] 2. Stuck-on headband, decorated with leather mosaic. Contemporary binding by Josep Cambras. 3. Sewn two-coloured headband on a leather core, with a bead on the edge and laced into the limp-vellum boards. The outer sewing (also in leather) ties down the core from the inside into the parchment. Limp-vellum binding model, renaissance style. 4. Metallic stuck-on headband… it’s a zipper! Contemporary binding by Begoña Cabero. 5. Simple wound headband, sewn on leather core with no bead. Gothic bookbinding sample, with leather-wooden boards. 6. Worked stuck-on headband, made with leather and thread. Contemporary binding by Begoña Cabero.

Types of endbands: sewn and stuck-on

As for their structure, we can divide headbands in two main groups: sewn and stuck-on.

Originally, sewn headbands were structurally functional, lacing the bookblock (the sheets) into the boards through a sewing (1st, 3rd and 5th examples in the previous image). This sewing involved the core of the headband (3rd and 5th), or it could also consist on a single thread (1st).

When bindings become more compact and sophisticated, headbands leave the goal to join boards and sheets, and limit their function to tighten the tail and head of the spine, providing a certain compactness through a sewing that ties down into the gatherings on the spine (see the ones below).

Sewn endband on an 18th century binding.

Here are the headbands of two volumes of a 1775 book (nothing less than a 3rd edition of Alambert & Diderot’s Encyclopédie!). These have a single dyed thread with a bead. They are sewn on a core made by several parchment layers, which provides it this rectangular and most distinguished shape (only parisians can be so chic… and what about the marbled edges matching colour?). The tailband on the right is broken and shows the core: some parchment layers, which are not joined into the boards. Just a few threads lace into the gatherings (two of them visible on the tailband at the right, already broken, on top). How much tightened is the endband into the book depends on the number of tiedowns attached into the gatherings, which is usually the minimum (among 3 and 6… the ones the bookbinder feels like at that moment).

But, why deny it, more than being a subjection for the bookblock, headbands are meant… to be nice! The same as stuck-on headbands (2nd, 4th and 6th examples), a german invention which appeared during the mid-fifteenth century, when other elements took over the functional role of the sewn ones; and they intended to be an ersatz, a fake, or a sort of a reminder with less functional weight.

Stuck-on headbands cohere the head and tail of the spine by simple adhesion. The oldest were still gathered into the boards, but today they are not linked to them anymore. The fact of the core being attached into the boards or not, is not evident at a glance, since they all intend to emulate sewn ones, and yet it represents a major formal difference. And, watch out! because we can even find endbands with a sewing which is not properly sewn into the boards or the gatherings, but merely into the core. Since this secondary sewing [3] doesn’t contribute at all to the lacing of the endband into the book, because it is merely pasted onto the spine, we should not classify them -structurally- as sewn endbands, but rather as stuck-on. And, to make it even more confusing, these last ones (with a sewing but stuck-on), can also be sewn with a sewing which is not the visible one! [4] I guess it’s clear now how necessary it is to establish a classification of endbands according to their structure, their function, since the conservation treatment basically lies on that. And describing them is horribly convoluted, as you have seen.

Stuck-on headbands

I’d like to focus now on the stuck-on headbands, which because of their lower category and meager joining, end up faring much worse (and I’ll come back to the classification in short).

No conservator hesitates when it comes to reproduce a sewn headband that’s been lost, or to consolidate a broken one, or to report it thoroughly: because it is worth it. And this is so because by taking care of them we not only preserve this historical and artistic component of the book, but we also recover a most relevant part of its skeleton.

Stolen snapshot of this magnificent example of woven stuck-on headband. Showing off the classical squares, gracefully combined with red leather, at the most nautical style. This 1889 endband is second to none… might have caused a sensation in the library! A piece of print paper with Mr. Cervantes is the silent spine lining on the invisible spine, being this patch the only attachment to the book. Pulling off books brings these pleasures.

But aren’t then the stuck-on headbands worth of it?!

Just because of their gewgaw nature doesn’t mean that they lack historical and stylistic value: we should regret not being able to preserve, reproduce or keep proper record of them, as much as for sewn endbands. Just like them they provide information about the bookbinding, and there are equally diverse styles and materials.

They can be made of leather, paper, fabric, thong, thread… any material able to be adhered (a metal zipper!). Replacing them systematically by the ones we can buy today by yards, impoverishes this rich spectrum and distorts the original artefact. Wouldn’t it be awkward to see a Louis XV with a spot patterned bow tie, instead of the embroidered white scarf?

Double stuck-on endband

A stuck-on headband is not necessarily implying that it is a good-for-nothing complement, especially when it has a part which binds to the boards, providing a more solid joining than the mere adhesion into the spine head and tail. It is adhered twice: onto the boards and onto the bookblock. The one in the following image belongs to the Municipal Archive of Alella (Barcelona, Spain), and it consists in a thong wrapped on green tawed leather, whose ends are stuck onto the boards. The thong was not prolonged into the boards, since its purpose was just to protrude beyond the head and tails of the edges.

Half binding in leather and paper, and parchment corners. c. 1867. Municicpal Archive of Alella (Barcelona). Detail of the stuck-on tailband, with a thong core wrapped in leather. Left: During dismantling. The alum tawed wrapper is extended onto the covers. Left: Pulling the book off. The endings of the leather wrapping are prolonged into the boards. Centre: Reproduction of the endbands: thong core wrapped in leather (and died green colour). Right: The new endband also replicates its structure, that’s why two cuts in the leather of the binding are necessary, to allow the leather lining of the endbands (which play the role of thongs) to reach the boards.

Loads of black, perdurable materials, and a sober hint of decoration in the corners… it’s a niche’s records book. Same binding as the previous image (front cover in the front inner box of the image), and a detail of its tailband (bigger rear image). Top: Before conservation. Bottom: After conservation. The headbands, the leather of the spine, the paper of the boards and the parchment corners have been replaced. Reproduction is an alternative to conservation, when the second exceeds the reasonable efforts justifiable for that object. The main issue is to keep the outcome truthful to the original, in form as well as in structure, and to keep duly record of the previous condition.

Despite the poor book was quite run-down, there’s nothing to blame on the endbands: there they stood, perfectly attached. In fact it is likely that they prevented the spine from breaking off completely. This happens sooner or later, after several unscrupulous attempts to take the book from the shelf by pulling the headband.

In my opinion, this double stuck-on endband would be even more efficient than those sewn only into the gatherings. Sewn joinings tend to be much more effective than stuck ones,[5] however, in this case there’s a leather thong joining the boards and the spine, and that conferes it a significant structural weight (and now the promised classification):

Endbands classification according to their structure

It is clear that each cell has loads of examples with a great variety of materials and particular features, and therefore its durability and structural value has to be considered in its context. The valuation in the fourth column is generic.

Hybrid endbands

I must admit I am jumping in the deep end, because I have never seen the hybrid headband myself! It would be such as stuck onto the boards and sewn into the textblock (and vice versa).

I put it in the table anyway because it is structurally possible, and even reasonable in the first case: pasted onto the boards. Nevertheless, the solution of sticking onto the spine but lacing into the boards, seems pretty awkward, I recognize that. Ligatus mentions a “sort of hybrid headband” in reference to Szirmai.[6] And, indeed, that example of gothic endband is both glued and tied down. Laced through the boards, and pasted down plus sewn into the spine. However, in my opinion the glued piece behaves more as a reinforcing of the sewing anchored into the gatherings, rather than as the main union of the endband onto the spine (I’ll say it again: where the two links coexist, in mobile areas, for me the leading one is the sewing, much more efficient and perdurable than the stuck)

The table intends to describe all the options, and there are so many types of endbands that I find it pretty possible that they existed without me knowing. If there is no such hybrid endband, we have the table as a conservation option guide, a way to evaluate which joinings are more perdurable than others, in case we need to reinforce endbands (doing this sort of hybridization).

I shall invite whoever provides me an example of the freaking hybrid headband, for a coffee at my studio. Just a coffee? A whole meal, at least! But I don’t mean that the same joining is both stuck-on and sewn (like Szirmai’s example), I mean that the attachment to the boards is one way, and into the bookblock the other way around.

Usual damages in stuck-on headbands

The most common stuck-on headband is only attached to the spine, like the one with nautical squares and Mr. Cervantes, and opposite to the previous example. It is not rare then that they end up quite dirty and broken, if they do remain attached at all. Endbands are in a most exposed position and they are expected to undergo great mobility; and stuck-on endbands are more vulnerable than sewn because of the lesser flexibility of adhesion compared to sewing.[7]

Conservation of stuck-on headbands

Since they are relatively recent and not much valued, in case of damage they are very often replaced by new ones. But finding the same ones might be quite difficult, as we are dealing with a medium-rate product. They were made of oddments or remnants from other crafts, it wasn’t something that you could buy for this particular purpose (like today). We can reproduce them, or restore them, depending on how much damaged they are, and how easy it is to replicate them.

Conservation of stuck-on headbands

If conservation is feasible, far much better! That’s clear.

It is as simple as pulling it off, cleaning it and rolling it again with that bit of displacement that will show a part in a better condition. If necessary an inner reinforcing can be added, and/or the core replaced by a new one. After all, the visible part is teeny, and there’s a major hidden part in perfect condition at our disposal, which we can re-use as if it was the spare wheel of a car. This is sustainability and historical criteria! The outcome is quite spectacular, because it is the very same endband but looks 100 years younger. I guess plastic surgeons would wish to achieve the dramatic improvements achieved at this conservation studio! (and please excuse my boasting). Hereunder two examples of woven stuck-on endbands conservation, both of them accomplished in a time lapse much shorter than the impossible mission required to find, or produce, the same piece of fabric

1) Example of adhered endband conservation:

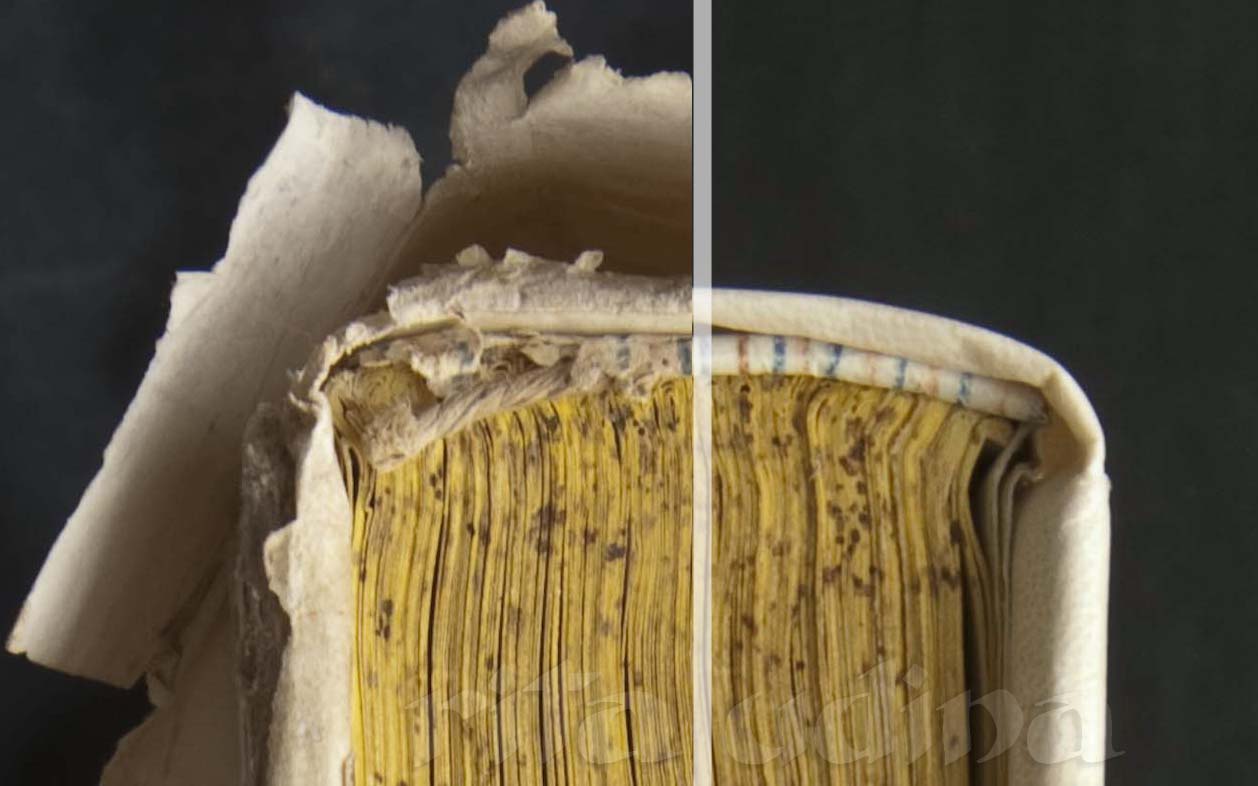

Romantic album, Museum of History of Barcelona (Spain). Before (left) and after (right) the conservation treatment. Full leather binding with princely gilded edges and with green and emerald striped woven endbands. It fits her owner perfectly: a posh little girl whose position and innocence helped her gather a naif but remarkable artistic compendium. More about the album and its conservation treatment.

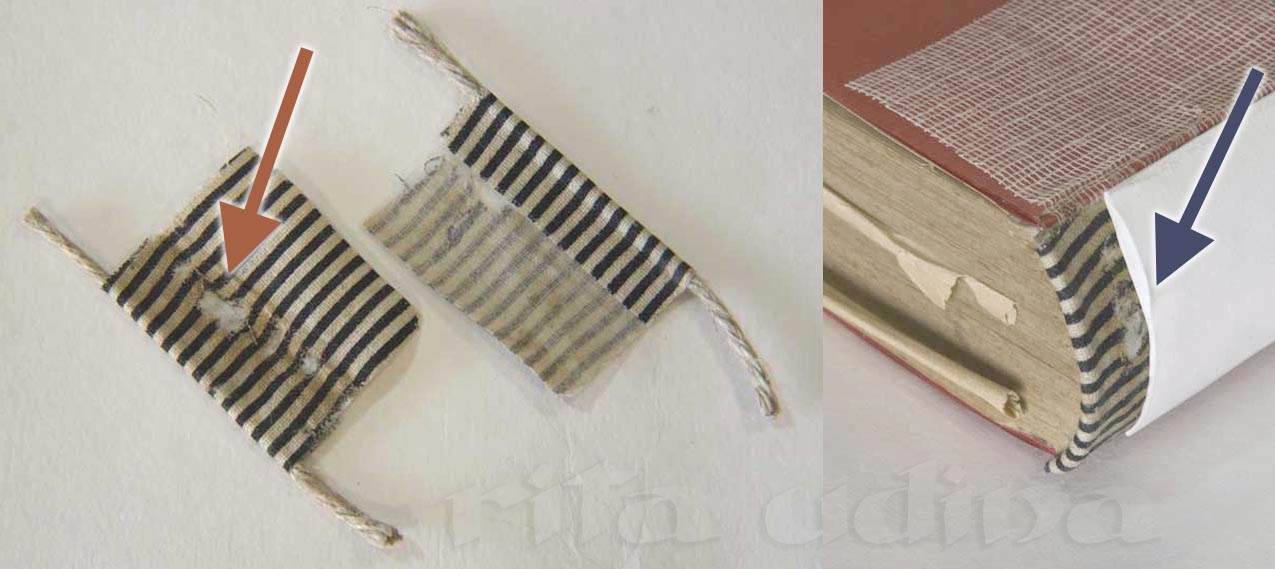

Left: original endband as extracted from the book. The core is made of leather, wrapped in a patterned fabric. Right: same endband after washing the fabric, lining it with a japanese tissue, and splitting it in two, in order to mount each piece on two new leather cores. From just the tailband two new endbands could be produces, since the headband was too damaged to use any significant piece. It is important to point that no matter how much younger the resulting endband looks, the fabric is still more than hundred years old, and quite damaged. The grain direction of the japanese tissue has been placed vertically, opposite to the core line, in order to obtain the major mechanical strength along the most vulnerable part, and prevent the endband from falling apart in case the fabric fails. The core is not visible at all and requires flexibility, it’s purely structural, that’s why there was no hesitation in replacing it. More details of the conservation of this album.

2) Another example of conservation of woven stuck-on endbands, with the same structural issues:

1906 half binding. Woven stuck-on headband with jail-striped pattern, the covers in severe black cloth, and dark green leather spine… no one will be surprised to know that this is the suit of a tax records book (from the Municipal Archive of Alella, Barcelona). Left: before conservation. The frayed fabric leaves the thong core exposed. Right: after conservation. The leather and fabric of the binding have been replaced by equal ones (those are easy to find), whereas the fabric of the endband has been preserved, showing a part in much better shape.

Left: Restored endbands of the previous book. The most frayed areas have been displaced. Right: Bookblock with the restored headband before binding it.

Stuck-on endbands reproduction

Magic is not always possible, especially when it comes to paper, much more fragile than fabric; but reproducing them doesn’t demand much time, if the pattern is simple. The issue is to keep it as close to what had been as possible, rather than replacing it systematically. When I can’t use the original endbands because of their poor condition, I deliver them -or the remnants- with the book, so that they are still there as a reference for researchers. T

1) The first study-case, a half bound book in leather and marbled paper, flat spine. A copy of theAnatomia Humani Corporis, by Godefridi Bidloo (1685).

Copy of Anatomia Humani Corporis, by Godefridi Bidloo (1685). It is half bound in leather and marbled paper, stuck-on paper endbands with oblique stripes and flat spine Top: As it arrived to the studio, and after undergoing an aggressive treatment that distorted some of the original elements, and was careless to preserve the endbands (probably already severely damaged). Bottom: The same book after the present conservation treatment. The elements in reasonably good condition have been infilled (leather, marbled papers) and the endbands have been reproduced, yet only some teeny remnants were preserved. I like oblique stripes: it’s stripes anyway, but they seem much less formal than the verticals.

I must say that the book had formerly suffered a very invasive treatment (about 40 years ago), with duct tape and other synthetic adhesives, which made it quite difficult to identify the real original structure. There was only a trace of the original endband, stuck into the inner spine:

Left: Back cover, tail edge, with sticking plaster and Aironfix (back colour) under the leather. Only a small trace of the endband (centre) was found half-stuck inside the spine, thanks to the neglect of the same bibliopath who “reinforced” the leather with self adhesive plastic. Right: The two reproduced endbands, and the original, in printed paper.

2) Another study case of paper stuck-on headband reproduction: An 1837 local census, also owned by the Municipal Archive of Alella. (see the heading image at the very top of this post, another one of the same endband).

Half parchment binding before and after conservation. Detail of the endband. Left, before conservation: the pattern of the paper is scarcely distinguishable and yet the core is visible, just about to fall apart, since it is attached to the book only by the adhesion of the paper. Right: Restored book with a reproduced binding: new parchment, new endbands, but same blue-red spirit.

It doesn’t seem likely (by date) that the same bookbinder who bound in severe mourning the tax records, maker of this other half binding: in clear parchment and vibrant multicoloured marbled paper. The edges tainted in bright yellow and the endbands in blue-red striped paper. Maybe the same blue and red stripes of his favourite football team? Census are documents consulted sick to death, and not even the resilient parchment could overcome the time challenge. Much less endurable is the paper stuck-on headband, from which the pattern is scarcely distinguishable. Nontheless the cord core is still there although almost falling apart, since it is attached to the book only by the adhesion of the paper. The conserved book has a reproduced binding: new parchment, new endbands, but same blue-red spirit (like Barça footbal team).

I just realized that this post also illustrates the delicate issue of criteria. On how we choose to preserve, or rather reproduce (either the whole thing or just some parts), depending on the artefact, its conservation condition… there is no mathematical formula, it depends on the value of things.

Sewing, sticking, stitching, sewing… I would never get tired of observing books. How do they function, what’s their structure, that thing that allows them to be consulted, to keep their pages compact and in order; and headbands are just such a tiny part… Isn’t the book the great invention of humanity?

Icons sewing and brush in the table are from Freepik.

Acknowledgement:

To the owners of these (and other) books, who have given me the chance to learn with them, and share this knowledge in this blog (in the order in which their books are shown): Private collection of the Encyclopédie, Alella Council (Barcelona, Spain), Museum of History of Barcelona (MUHBA) and the Royal Academy of Pharmacy of Catalunya (RAFC, Barcelona).

Also to the bookbinders who opened their binderies (Josep Cambras, Begoña Cabero) and to Arsenio Sánchez, conservator, that, only because he is such good person, wise and generous doesn’t make me feel awfully jealous about his collection of sample bindings from all styles and times.

Ligatus, for providing such an excellent online and free resource (spanish translation is needed!).

Dedicated to:

This post is dedicated to my favourite writer, author of delirious texts and bearer of the most blue-red heart, like the last endband. Thanks for writing me, and thanks for reading me.

Footnotes:

[1] And I speak about the standard book, since artistic or craft bookbinding is very much into recovering ancient techniques, and that’s why it is not surprising to find this sort of “functional-headbands” also in notebooks and other handmade products, in the shape of coptic, islamic and gothic sewings, among others.

[2] This one, the 3rd and 5th, all of them made in courses lead by Arsenio Sánchez Hernampérez, a constant source of inspiration. Thanks a lot Arsenio!

[3] And this doesn’t mean that all endbands having a secondary sewing are stuck-on endbands.

[4] I mean those stuck-on headbands which have a sewing/braid in their support. Many bookbinders choose to stitch them with thread into the spine, instead of pasting it.

[5] Udina, Rita. “La unió fa la força? Estudi de la consistència de les estructures dels llibres i propostes d’intervenció” published at Únicum (#14), ed. ESCRBCC (Escola Superior de Conservació i Restauració de Béns Culturals de Catalunya), pages 63-86 (catalan) and 199-210 (spanish) (2015). D.L.: B-16094-2002, ISSN:1579-3613.

[6]  That’s the literal definition by Szirmai: one or two strips or a roll of parchment; the support is either independent of the spine lining (b), or it is wrapped into the lining and glued as a unit into the spine (c). Initially the supports were anchored into the board corners, but later this firm attachment between the bookblock and the cover was dropped and the endband supports were used as mere cores”. The Archaeology of Medieval bookbinding, J.A. Szirmai, ed. Ashgate, 1999.

That’s the literal definition by Szirmai: one or two strips or a roll of parchment; the support is either independent of the spine lining (b), or it is wrapped into the lining and glued as a unit into the spine (c). Initially the supports were anchored into the board corners, but later this firm attachment between the bookblock and the cover was dropped and the endband supports were used as mere cores”. The Archaeology of Medieval bookbinding, J.A. Szirmai, ed. Ashgate, 1999.

[7] Sewn elements, especially in mobile areas, tend to be more efficient and durable than adhered ones (being other factors equal).