Unlocking St. Anthony’s locked manuscript

Tony, Tony, come around,

something’s lost and can’t be found!

No matter how vehemently I prayed to Saint Anthony, no key to unlock an 18th century manuscript could be found.

It is hard to imagine that in 1766 real estate lobbies were as much of a daily concern for ordinary citizens as they are nowadays, and yet this is a clear example of how little things have changed. Detailed data from the building industry in Catalonia[0] was kept in the utmost secrecy by means of literally locking the manuscript with an iron safety lock inlayed in the back cover of the binding.

Either to access its valuable information, or because the key was lost, the front cover of the book had at some point been broken in order to release the bolt clasp without Saint Anthony’s blessing (or the key).

Saint Anthony is the patron saint of bricklayers –at least in Spain– and a holy card with his image was placed on the back pastedown to protect the lock, but not the binding, which was quite damaged after these efforts. It seems quite naïve today to think that a robust iron lock was deemed to be sufficiently effective when it had been inserted into such flimsy cardboard. I wonder why they didn’t at least use wooden boards.

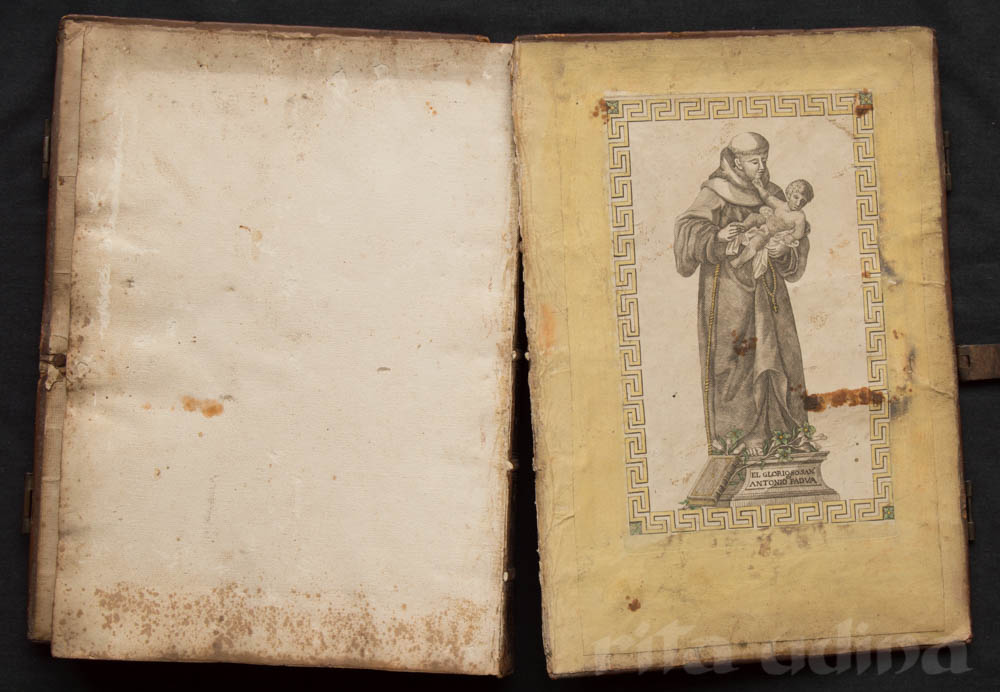

Before treatment: Pastedown with Saint Anthony’s holy card (patron of bricklayers, masons, architects and constructors), covering the lock. The board is almost loose due to the weight of the iron lock, under the holy card, whose rust went beyond the paper (right).

Many unknowns arise from this handwritten list of masons: the missing key, missing folios, a yellow based pigment in the back pastedown[1] and others; but I’d like to share the certainties now providing some details of the conservation treatment, and more specifically of the key issue: how to unlock the locked manuscript.

Bookbinding description

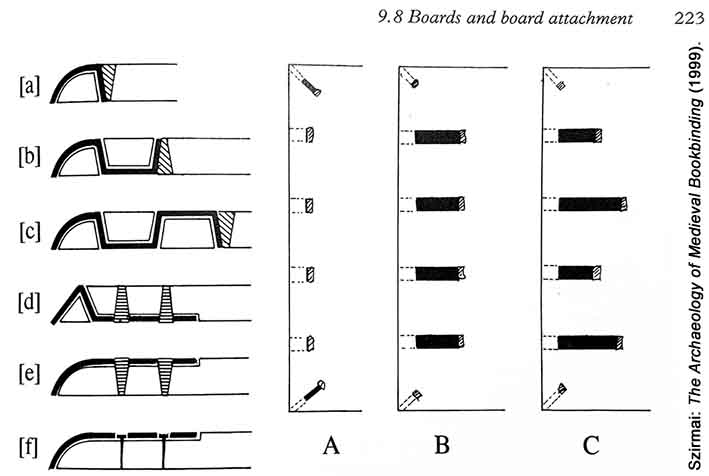

The manuscript was sewn on five tawed leather thongs laced on cardboards. The style corresponded closely to renaissance bindings[2]: full binding with raised bands on a tight spine, rectangular blind tooling decoration with floral elements (also in the spine), brass bosses and clasps… and an iron safety lock inside the back cover! As for the structure, the use of cardboard instead of wooden boards is one of the elements that differs from gothic binding features and is similar to renaissance characteristics[3].

Before (top image) and after conservation (bottom). The bolt clasp locked on the back cover (left) has been unlocked and placed back in the front cover (right).

The lock consisted of two pieces: one inside the back cover, not visible except through the keyhole, and the corresponding bolt, nailed onto the front cover as a clasp. However this piece was detached from the front cover, and remained lodged into the back cover lock.

The numerous attempts to open the book without the key might have caused the front cover to come apart. The back cover was quite loose too due to the weight of the iron lock. The metal components were visibly rusted, as well as some parts of St. Anthony’s holy card (and under layers).

Proposed treatment

The main goal was to restore the utility of the lock and solve the structural issues derived from the fact that the covers were loose. Although the structural damage was severe, the leather was in relatively good condition and thus the idea to not dismount the whole binding prevailed rather than taking apart bosses, detaching the leather, etcetera.

The text block was also quite well preserved, hence dry cleaning was the major treatment suggested for the folios, and to preclude any major disassembling.

Regarding the binding structure a dilemma emerged: whether to keep the tight spine or to add a hollow. Apart from the fair condition of the spine itself, the need to somehow extend the broken thongs implied detaching it and making some changes to it. Once the lock was fixed, each cover should bear the weight of an iron piece (plus 7 brass ones) so the lacing of the text block to the covers needed to be resilient enough and still not protrude much.

Nevertheless in this case it was deemed not strictly necessary or particularly beneficial to change the spine structure, even though detaching the leather from the spine to permit consolidation of the structure seemed unavoidable.

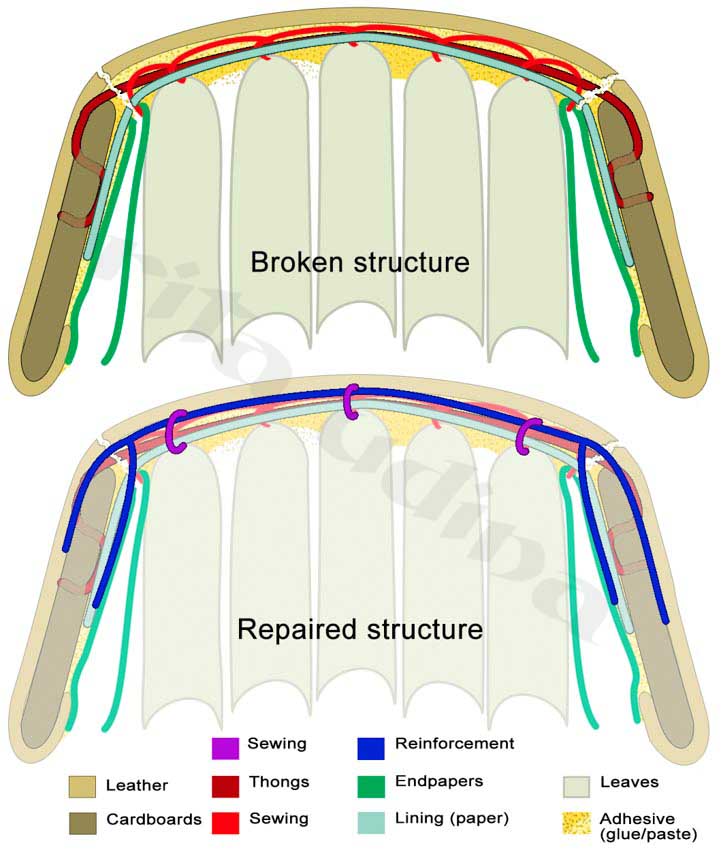

After doing so, reinforcements were to be added between the thongs whose extensions would be pasted onto the covers. In movable areas (such as the spine) it is more effective and durable to use sewn or laced solutions versus pasted[4], but this tenet could only be partially achieved (sewing into the spine, but pasting onto the covers) due to the nature of the boards and the features and condition of the binding. Weighing up pros and cons, however, the benefits of this partial solution were on the overall larger than the drawbacks.

| Joint | Original (unbroken) | Restored | Structural value |

| Text block gatherings. | Sewn on thongs (red in the illustration). | Sewn on thongs (red in the illustration), and

Sewn onto the spine reinforcement (purple in the illustration). |

Very strong. The added materials (dark blue in the illustration) do not lessen the strength or flexibility. |

| Covers – text block | Sewn: Thongs laced into the covers (burgundy in the illustration), and

Pasted: Mainly through the spine lining (pale blue in the illustration and shown two images further) and the pastedowns (green in the illustration) also contribute to the attachment. |

Pasted: synthetic spine reinforcement (dark blue in the illustration and shown in next image) pasted onto the covers. | An extension of the non-woven tissue sewn into the spine takes the place of the broken thongs and allows the joining to the covers. It provides a larger joint than 5 local thongs since it is all along the cover. It can bear the weight of heavy boards and it is flexible enough to enable handling. |

As for the lock, after fruitless attempts to fix it without disassembling it, the removal of the pastedown would make the lock visible and hopefully widen the range of possible solutions.

Conservation details: the joint between covers and text block

The leather was removed from the spine with a scalpel, and next six Reemay® strips were sewn into the spine, between the thongs. The strips overlapped the covers by about 5 cm, has they were wider than the spine. Then the extended flaps from the strips were pasted onto the boards. I usually do it by inserting them into the cardboards, after splitting the joint edge of the cover (as a sort of manual board slotting[5]); but that was rather difficult because of the nature of the cardboard handmade from rags as the entangled structure thwarted any attempt to do the splitting properly.

Therefore I chose to paste four of the strips on the outer side of the cover (under the leather), and the rest in the inner side. Recovering the laced structure in the union covers-spine was deemed not feasible if the leather was to remain mostly untouched, and the adhered reinforcement is expected to be strong enough.

Spine after removing the leather and sewing in Reemay© strips between the broken thongs. The extension of the strips is pasted onto the cover.

Once the structure was recovered the leather from the spine was pasted back into its place with acrylic adhesive and the joints and losses were infilled with Japanese paper and retouched with acrylic paints.

Conservation details: the lock

Saint Anthony was carefully removed from the back cover but we did not succeed in puzzling out the mechanism of the lock, since it was enclosed in a solid iron cluster with very narrow accesses.

Back cover (left) after removing Saint Anthony’s holy card and other laid papers pasted onto it (right). The lock was thoroughly rusted, as could be guessed in the holy card, and an inner cluster prevented any attempt to understand the inner mechanism. At the right side of the cover, the original paper lining coming from the spine.

Rust was mechanically removed and some lubricant applied in this inner cell, with the happy result that it moved again. Anyhow the key was still missing, and despite the progress it wasn’t clear whether it could function normally again or not, therefore a tiny piece of Mylar® plastic film was placed inside to block it and prevent it from locking again.

All the iron pieces were protected with Paraloid B-72 in order to prevent further rusting. The bolt clasp was treated with an acid tannic solution[6], and also varnished.

Inner back cover, after removing the pastedown. Left: The bolt clasp is still stuck into the lock and both pieces are visibly rusted. Right: Unlocked lock and bolt clasp, after removing rust.

The front cover was significantly damaged where the bolt clasp had been ripped out so it was consolidated and nailed back into its original position.

Finally the restored pastedowns were pasted onto the covers, hopefully with Saint Anthony’s blessing.

Footnotes:

[0] “Llibre de las Ordinacions dels Fadrins Mestras de Cassas de la Present Ciutat de Barna. Llibre de cardensa dels ioves mestre de casas de 1766″ (old catalan) could be translated as “Book of the Orderings of the Master Builders of Houses of the Present City of Barcelona. Credentials for young Builders of Houses in 1766”. See Spanish or Catalan version of this post, to know more about the etymology of this title.

[1] It is not the first time that I have seen a yellow paint like this, the other times it was on the binding surface, with the same apparent lack of artistic intentions. The possibility that it was a sulphur based paint with disinfectant purposes seems quite feasible.

[2] Herrera Morillas, José Luis. Las encuadernaciones artísticas del siglo XVI en el Fondo Antiguo Digital de la Universidad de Sevilla. Boletín de la Asociación Andaluza de Bibliotecarios. N°110, Julio-Diciembre 2015, pp. 56-103.

[3] Lacing paths match the described gothic structure by Szirmai in figure 9.33 ([b] and [B]) on page 223: each sewing support is laced through two holes perpendicular to the spine. J.A. Szirmai: The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. Ed. Ashgate, 1999.

[4] Udina, Rita. “Study of the strength of book structures and intervention proposals” (abstract in English, full text in Spanish and Catalan). Unicum #14. June, 2015, ed. ESCRBCC. Pages 63-86 and 199-210. Online pdf.

[5] Zimmern, Friederike: Board Slotting: A Machine-Supported Book Conservation Method. AIC, The Book and Paper Group Annual. Volume 19 (2000). Accessed 1st July 2018.

[6] Logan, Judy: Tannic Acid Coating for Rusted Iron Artefacts. Canadian Conservation Institute Notes, Series 9 (metals), part 5. Accessed 1st July, 2018.

Acknowledgement:

- Library and Historical archive of the Architects’ Association of Catalonia (CoAC), who trusted me for the conservation of such a special book, and many other beautiful artefacts.

- Jaume Xarrié, antiquarian, builder and former landlord of my studio. Dedicating him this short conservation report cannot possibly show how grateful I am for feeling always protected and helped. Mr. Xarrié always has the key to solve any problem. Thank you!

- Neil Forrest, for his help in proofreading the text.

Publication in IIC News in Conservation:

We are proud to tell that this post has been published in the IIC bulletin News in Conservation (issue 67, August 2018, pp. 11-13). Thanks also to Sharra Grow to make it possible.

Filter post by:

Unlocking St. Anthony’s locked manuscript

Tony, Tony, come around,

something’s lost and can’t be found!

No matter how vehemently I prayed to Saint Anthony, no key to unlock an 18th century manuscript could be found.

It is hard to imagine that in 1766 real estate lobbies were as much of a daily concern for ordinary citizens as they are nowadays, and yet this is a clear example of how little things have changed. Detailed data from the building industry in Catalonia[0] was kept in the utmost secrecy by means of literally locking the manuscript with an iron safety lock inlayed in the back cover of the binding.

Either to access its valuable information, or because the key was lost, the front cover of the book had at some point been broken in order to release the bolt clasp without Saint Anthony’s blessing (or the key).

Saint Anthony is the patron saint of bricklayers –at least in Spain– and a holy card with his image was placed on the back pastedown to protect the lock, but not the binding, which was quite damaged after these efforts. It seems quite naïve today to think that a robust iron lock was deemed to be sufficiently effective when it had been inserted into such flimsy cardboard. I wonder why they didn’t at least use wooden boards.

Before treatment: Pastedown with Saint Anthony’s holy card (patron of bricklayers, masons, architects and constructors), covering the lock. The board is almost loose due to the weight of the iron lock, under the holy card, whose rust went beyond the paper (right).

Many unknowns arise from this handwritten list of masons: the missing key, missing folios, a yellow based pigment in the back pastedown[1] and others; but I’d like to share the certainties now providing some details of the conservation treatment, and more specifically of the key issue: how to unlock the locked manuscript.

Bookbinding description

The manuscript was sewn on five tawed leather thongs laced on cardboards. The style corresponded closely to renaissance bindings[2]: full binding with raised bands on a tight spine, rectangular blind tooling decoration with floral elements (also in the spine), brass bosses and clasps… and an iron safety lock inside the back cover! As for the structure, the use of cardboard instead of wooden boards is one of the elements that differs from gothic binding features and is similar to renaissance characteristics[3].

Before (top image) and after conservation (bottom). The bolt clasp locked on the back cover (left) has been unlocked and placed back in the front cover (right).

The lock consisted of two pieces: one inside the back cover, not visible except through the keyhole, and the corresponding bolt, nailed onto the front cover as a clasp. However this piece was detached from the front cover, and remained lodged into the back cover lock.

The numerous attempts to open the book without the key might have caused the front cover to come apart. The back cover was quite loose too due to the weight of the iron lock. The metal components were visibly rusted, as well as some parts of St. Anthony’s holy card (and under layers).

Proposed treatment

The main goal was to restore the utility of the lock and solve the structural issues derived from the fact that the covers were loose. Although the structural damage was severe, the leather was in relatively good condition and thus the idea to not dismount the whole binding prevailed rather than taking apart bosses, detaching the leather, etcetera.

The text block was also quite well preserved, hence dry cleaning was the major treatment suggested for the folios, and to preclude any major disassembling.

Regarding the binding structure a dilemma emerged: whether to keep the tight spine or to add a hollow. Apart from the fair condition of the spine itself, the need to somehow extend the broken thongs implied detaching it and making some changes to it. Once the lock was fixed, each cover should bear the weight of an iron piece (plus 7 brass ones) so the lacing of the text block to the covers needed to be resilient enough and still not protrude much.

Nevertheless in this case it was deemed not strictly necessary or particularly beneficial to change the spine structure, even though detaching the leather from the spine to permit consolidation of the structure seemed unavoidable.

After doing so, reinforcements were to be added between the thongs whose extensions would be pasted onto the covers. In movable areas (such as the spine) it is more effective and durable to use sewn or laced solutions versus pasted[4], but this tenet could only be partially achieved (sewing into the spine, but pasting onto the covers) due to the nature of the boards and the features and condition of the binding. Weighing up pros and cons, however, the benefits of this partial solution were on the overall larger than the drawbacks.

| Joint | Original (unbroken) | Restored | Structural value |

| Text block gatherings. | Sewn on thongs (red in the illustration). | Sewn on thongs (red in the illustration), and

Sewn onto the spine reinforcement (purple in the illustration). |

Very strong. The added materials (dark blue in the illustration) do not lessen the strength or flexibility. |

| Covers – text block | Sewn: Thongs laced into the covers (burgundy in the illustration), and

Pasted: Mainly through the spine lining (pale blue in the illustration and shown two images further) and the pastedowns (green in the illustration) also contribute to the attachment. |

Pasted: synthetic spine reinforcement (dark blue in the illustration and shown in next image) pasted onto the covers. | An extension of the non-woven tissue sewn into the spine takes the place of the broken thongs and allows the joining to the covers. It provides a larger joint than 5 local thongs since it is all along the cover. It can bear the weight of heavy boards and it is flexible enough to enable handling. |

As for the lock, after fruitless attempts to fix it without disassembling it, the removal of the pastedown would make the lock visible and hopefully widen the range of possible solutions.

Conservation details: the joint between covers and text block

The leather was removed from the spine with a scalpel, and next six Reemay® strips were sewn into the spine, between the thongs. The strips overlapped the covers by about 5 cm, has they were wider than the spine. Then the extended flaps from the strips were pasted onto the boards. I usually do it by inserting them into the cardboards, after splitting the joint edge of the cover (as a sort of manual board slotting[5]); but that was rather difficult because of the nature of the cardboard handmade from rags as the entangled structure thwarted any attempt to do the splitting properly.

Therefore I chose to paste four of the strips on the outer side of the cover (under the leather), and the rest in the inner side. Recovering the laced structure in the union covers-spine was deemed not feasible if the leather was to remain mostly untouched, and the adhered reinforcement is expected to be strong enough.

Spine after removing the leather and sewing in Reemay© strips between the broken thongs. The extension of the strips is pasted onto the cover.

Once the structure was recovered the leather from the spine was pasted back into its place with acrylic adhesive and the joints and losses were infilled with Japanese paper and retouched with acrylic paints.

Conservation details: the lock

Saint Anthony was carefully removed from the back cover but we did not succeed in puzzling out the mechanism of the lock, since it was enclosed in a solid iron cluster with very narrow accesses.

Back cover (left) after removing Saint Anthony’s holy card and other laid papers pasted onto it (right). The lock was thoroughly rusted, as could be guessed in the holy card, and an inner cluster prevented any attempt to understand the inner mechanism. At the right side of the cover, the original paper lining coming from the spine.

Rust was mechanically removed and some lubricant applied in this inner cell, with the happy result that it moved again. Anyhow the key was still missing, and despite the progress it wasn’t clear whether it could function normally again or not, therefore a tiny piece of Mylar® plastic film was placed inside to block it and prevent it from locking again.

All the iron pieces were protected with Paraloid B-72 in order to prevent further rusting. The bolt clasp was treated with an acid tannic solution[6], and also varnished.

Inner back cover, after removing the pastedown. Left: The bolt clasp is still stuck into the lock and both pieces are visibly rusted. Right: Unlocked lock and bolt clasp, after removing rust.

The front cover was significantly damaged where the bolt clasp had been ripped out so it was consolidated and nailed back into its original position.

Finally the restored pastedowns were pasted onto the covers, hopefully with Saint Anthony’s blessing.

Footnotes:

[0] “Llibre de las Ordinacions dels Fadrins Mestras de Cassas de la Present Ciutat de Barna. Llibre de cardensa dels ioves mestre de casas de 1766″ (old catalan) could be translated as “Book of the Orderings of the Master Builders of Houses of the Present City of Barcelona. Credentials for young Builders of Houses in 1766”. See Spanish or Catalan version of this post, to know more about the etymology of this title.

[1] It is not the first time that I have seen a yellow paint like this, the other times it was on the binding surface, with the same apparent lack of artistic intentions. The possibility that it was a sulphur based paint with disinfectant purposes seems quite feasible.

[2] Herrera Morillas, José Luis. Las encuadernaciones artísticas del siglo XVI en el Fondo Antiguo Digital de la Universidad de Sevilla. Boletín de la Asociación Andaluza de Bibliotecarios. N°110, Julio-Diciembre 2015, pp. 56-103.

[3] Lacing paths match the described gothic structure by Szirmai in figure 9.33 ([b] and [B]) on page 223: each sewing support is laced through two holes perpendicular to the spine. J.A. Szirmai: The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. Ed. Ashgate, 1999.

[4] Udina, Rita. “Study of the strength of book structures and intervention proposals” (abstract in English, full text in Spanish and Catalan). Unicum #14. June, 2015, ed. ESCRBCC. Pages 63-86 and 199-210. Online pdf.

[5] Zimmern, Friederike: Board Slotting: A Machine-Supported Book Conservation Method. AIC, The Book and Paper Group Annual. Volume 19 (2000). Accessed 1st July 2018.

[6] Logan, Judy: Tannic Acid Coating for Rusted Iron Artefacts. Canadian Conservation Institute Notes, Series 9 (metals), part 5. Accessed 1st July, 2018.

Acknowledgement:

- Library and Historical archive of the Architects’ Association of Catalonia (CoAC), who trusted me for the conservation of such a special book, and many other beautiful artefacts.

- Jaume Xarrié, antiquarian, builder and former landlord of my studio. Dedicating him this short conservation report cannot possibly show how grateful I am for feeling always protected and helped. Mr. Xarrié always has the key to solve any problem. Thank you!

- Neil Forrest, for his help in proofreading the text.

Publication in IIC News in Conservation:

We are proud to tell that this post has been published in the IIC bulletin News in Conservation (issue 67, August 2018, pp. 11-13). Thanks also to Sharra Grow to make it possible.