Onion skin paper: History, Uses, Composition and Conservation

Onion skin paper—is it or is it not a tracing paper? This single thought crossed my mind the first time I had to face the conservation treatment of an onion skin paper document. Far from being concerned with nomenclature or classification, I was rather worried about anticipating the setbacks that could arise during the conservation treatment.

Characteristics of onion skin paper

Still today, I dare not make a statement, as there is no clear consensus, but it can be said confidently that onion skin paper is lightweight and translucent… and certainly not made from onion skin! The name comes from its resemblance to the delicate, transparent layers of the vegetable. Admittedly, terminology is open to interpretation and does not always contribute to a better understanding of the topic. In the end, what’s the point of naming and classifying if we do not understand the behavior of the paper, whether for preservation or when applying conservation treatments?

In the latest artefact I was commissioned to conserve, the only certainty was that it was, indeed, onion skin paper—confirmed beyond doubt by the watermark, which stated: “Edgeworth Onion Skin Paper. Rag Content. Valley Paper Co. USA” .

A great opportunity to share what I’ve discovered about onion skin paper and perhaps shed some light on the matter. Or who knows—maybe even spark further insights? Feel free to share your thoughts, as I’m genuinely interested in the topic; all contributions are welcome!

Onion skin paper watermark under transmitted light. Edgeworth Onion Skin. Rag content. Valley Paper Co. EE.UU .

According to general references, it is not only thin and translucent, but a strong and durable paper (1). The indistinct use of the term tracing paper is due to the obvious similarities with it, which enable tracing on onion skin paper as well. In my opinion they both have similar behaviour towards water, that is predictably evil, somehow like a gremlin paper would behave.

History

I wish I had found more precise information on the origin of onion skin paper, which seems to have first been manufactured in the mid-19th century. Progress and specialization in the industry, along with the growing demand for paper for administrative purposes, might have driven its production, which was fully industrial. It was widely marketed between 1920 and 1970. But who knows if there was a specific trigger? Someone who found useful writing on a rolling paper and exploited the idea with variations? …what if that person was a spy called Mata Hari?

Putting imagination aside, one of the oldest producers I’ve found online is Esleeck Manufacturer Co. (1898–1987), specialising in onion skin paper (2). The Amherst Libraries of the University of Massachusetts hold 4.5 linear feet of company records, quietly awaiting someone to unravel their secrets. If Esleeck were not the first to produce it in the USA, I’m convinced that the inventor of their flagship product is mentioned somewhere among their paperwork.

But I have also found examples much closer to home, such as Onion skin Barcino, paper, with some images a few paragraphs ahead Barcino paper takes me back to rolling papers. It turns out that the earliest rolling paper dates from the 19th century (3) and was called Catalan paper, or Barcelona paper (i.e. the Roman Barcino), as it was first produced in Catalonia and exported from there to the Americas (4) . Manufacture of onion skin paper was likely developed by an industry eager to engineer solutions to the demands of the time, driven by a desire to create new products for the market. Perhaps Mata Hari had nothing to do with it, but the link between these two types of paper is not as far-fetched as it might seem. In any case, the dating of onion skin paper in Europe remains unresolved, and I take pride in the fact that paper itself was introduced to the West precisely through the Mediterranean corridor.

Uses and Applications

Its lightness, thinness, transparency, strength, and durability have made it highly valuable for very specific uses.

For instance, it was widely used for copying and duplicating handwritten—but especially typewritten—documents. The paper’s fineness allowed pressure to transfer effectively onto carbon paper, ensuring a precise duplicate on a second sheet of onion skin paper, while its strength prevented the top sheet from tearing under the impact of metal typewriter keys. Up to five copies could be made simultaneously by alternating layers of carbon and onion skin paper, which explains why it needed to be so thin. By the way: did you know that the abbreviation “cc” of emails meaning in copy comes precisely from carbon copy—carbon paper, or copy paper? (5).

The copying process on a typewriter involved placing a sheet of carbon paper (dark blue in the image) between two sheets of onion skin paper. Photo: Richard Polt.

A significant portion of company records from this period were produced on this material. Being lightweight, thin, and durable, it was an ideal material for non-ephemeral archival documentation, helping to save storage space, reduce weight, and minimise future conservation challenges in archival repositories.

Due to its lightness, onion skin paper was also widely used for airmail correspondence—back when mail was a physical material rather than intangible bytes. However, its thinness was not without drawbacks: it could only be written or drawn on one side and was impractical for most printing processes.

“Barcino” onion skin paper for airmail purposes. Photo: Lola Espinosa (oficio-blog.blogspot).

Watermark on Barcino onion skin paper, also for airmail purposes. Photo: watermarks.info

Its transparency has been widely utilised for anything involving tracing, such as technical and architectural drawings. It was also essential in the early process of creating animated films, which even led to the term onionskinning to describe this stage of animation.

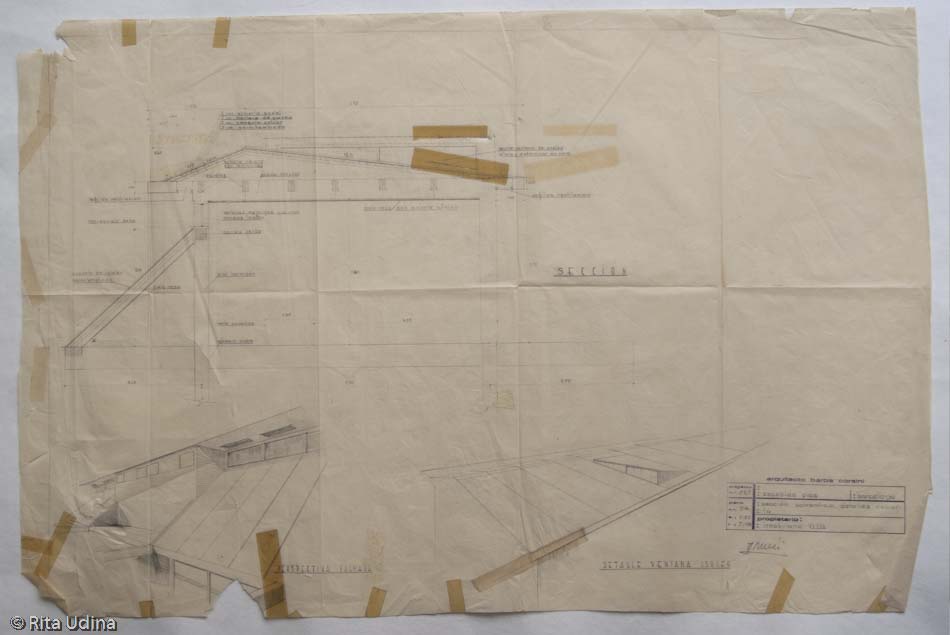

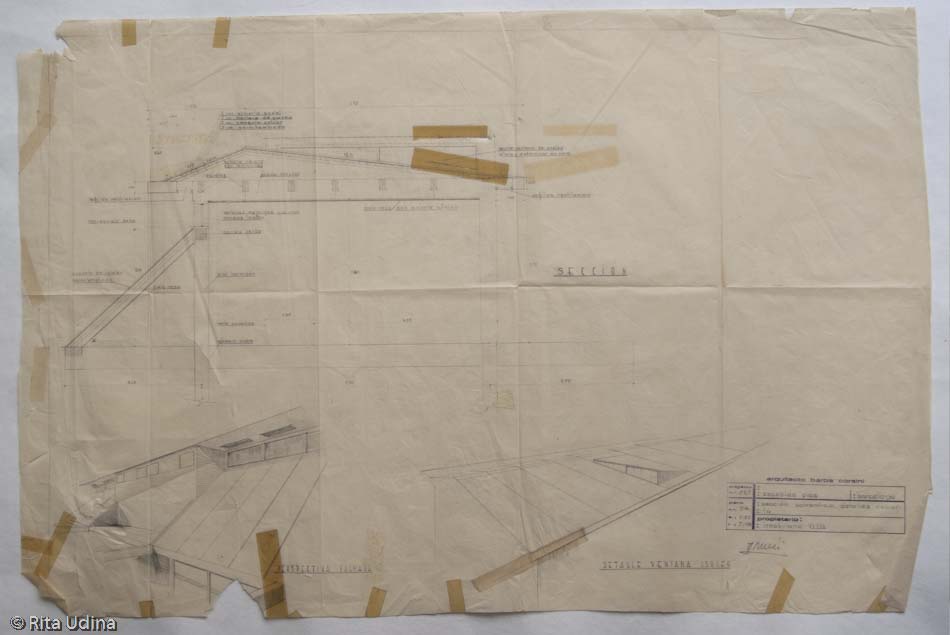

Architectural drawing before (left) and after (right) conservation, showing stains caused by the oxidation of the greasy adhesive from those damned pressure-sensitive tapes. Unfortunately, the drawing’s linework overlapped the tape, requiring its removal, cleaning of the adhesive residue, and reapplication using a non-original adhesive.

Project for the Pies Schools by architect Barba Corsini, c. 1960. 1960. Graphite pencil on onion skin paper.

John M. Lounsbery (1911–1976) from the Walt Disney Studios, creating animations over a light table (visible as the circle below). Source: Disney.fandom.

This lightweight, crisp paper, endowed with remarkable mechanical strength, is also ideal for folding into three-dimensional objects—the Japanese art of origami. If ever struggling to flatten an onion skin document, a conservator can always resort to folding it into a paper plane and sending it back to the client with a newfound flying function, should the original one prove beyond recovery!

Origami: Propeller plane made of two pieces of folded onion skin paper by Seiji Nishikawa. Photo: Gilad’s Origami place.

In book publishing, onion skin paper is often used as a protective interleaf for illustrations or prints. Its extreme thinness makes creases almost inevitable, and since it comes into direct contact with oil-based printing inks, it is not uncommon to find it discoloured. Oxidation can also result from adjacent papers of lower quality, further contributing to discolouration.

It is also used as a book dust jacket, particularly in more modern art editions. In these cases, it tends to be more transparent (and glossier) to allow the cover design to remain visible or, at the very least, the title to be legible.

Characteristics

Quality and Composition

There are different qualities of onion skin paper, which, as mentioned, is generally of medium to high quality. The best quality is achieved when the paper pulp is made from rag fibres (cotton or linen). This was indicated by terms such as “rag content,” and if no further details were provided, it meant the paper contained at least 25% cotton fibres (1). If the percentage was higher, it was explicitly stated (e.g., “100% cotton” or the specific proportion). Needless to say, when high-quality fibres are used, the resulting pulp is also more durable and permanent. In lower-grade papers, the remaining pulp would consist of wood fibres which have been chemically treated to remove lignin—which causes poor ageing—and bleached to have a white appearance.

Physical Characteristics

The content of rag fibres is what endows onion skin paper with its remarkable mechanical strength. It allows for typing and heavy folding in origami, for example. This is despite its minimal thickness (ranging between 9 and 35 gsm, approximately), and considering that for the paper to be so thin, intensive calendaring of the paper pulp is required during production. I recently heard a paper miller say that prolonged fibre beating weakens the fibre while strengthening the paper, as defibrillation promotes bonding with neighbouring fibres rather than shortening them. And this is indeed the case, as onion skin paper—at least in my opinion—has greater resistance than many tracing papers, which, despite being thicker, are extremely vulnerable to tearing along the grain. In contrast, onion skin paper tends to be less transparent than most tracing papers. It could be said that onion skin paper is a less advanced version of tracing paper, or its technological predecessor. The fibre compactness is lower, and consequently, it is less transparent and more porous than tracing paper (in general terms).

Sizing and Finishing

Sizings used in onion skin paper production could vary: gelatine, starch (6), rosin or others (1); and the finish could be cockled or smooth. If the paper was left to dry without tension during the final production phase, the surface would become cockled, more porous and slightly wavy. The cockle finish is so called in reference to the wavy surface of the shell. For a smooth finish, additional calendaring during the drying phase—supercalendering(1)—is required. The heat and pressure reduce the voids between fibres, resulting in a more transparent, even glossy. In my opinion, these are harder to distinguish from proper tracing paper, especially if their rag content is minimal or even absent.

The finish largely determines how ink settles on or is absorbed by the paper surface. The more porous the paper, the quicker the ink will be absorbed—meaning the surface dries faster. That’s why all the examples shown here of writing paper, whether for typing or handwriting, have a cockle finish. On the other hand, a very smooth or even glossy surface results in sharper definition of the writing lines or inked areas. If we succeed in preventing such a thin, slow-absorbing paper from warping due to ink moisture or from being accidentally smudged before the ink has dried, then—under these ideal conditions—the ink will spread less along the fibres, resulting in sharper lines. In the example of the dust jacket in the artist’s book, which has a very smooth finish, the paper itself is neither written nor printed on; it is the book cover that carries the text. In the example of the dust jacket in the artist’s book, which has a very smooth finish, the paper itself is neither written nor printed on; it is the book cover that carries the text.

Behaviour and analogies with tracing paper

These physical properties—namely, the fibre length and the compactness between them—largely determine the paper’s behaviour when exposed to water. Onion skin paper expands much more than a “normal” paper (like many tracing papers), and air-drying it often leads to the worst possible outcomes, because as the water evaporates, the paper shrinks uncontrollably, or in a manner we would not prefer.

If we group tracing papers by how their translucency is achieved, we can roughly distinguish three categories(7): In the first type, also called “natural tracing paper”, transparency is achieved mechanically—either through over-beating of the fibres, by applying high pressure during calendaring, or by a combination of both. In the second category, transparency is obtained through chemical treatment of the paper pulp, in which the cellulose undergoes a chemical digestion that transforms it into a colloidal by-product. This chemical treatment is not the same as that used for the delignification of wood pulp mentioned earlier, and consequently, onion skin paper (whether made from wood pulp or rag fibres) could not belong to this group. In the third group, transparency is achieved by impregnating the paper with a coating, (8) usually an oil or wax, which is again quite different from the properties of onion skin paper.

In conclusion, if onion skin paper were to be considered a type of tracing paper, it would fall within the first group, since its transparency is due to mechanical action (calendaring and beating). The main difference between onion skin paper and natural tracing paper lies in the fibre length—in other words, in the less intensive fibre beating during papermaking.

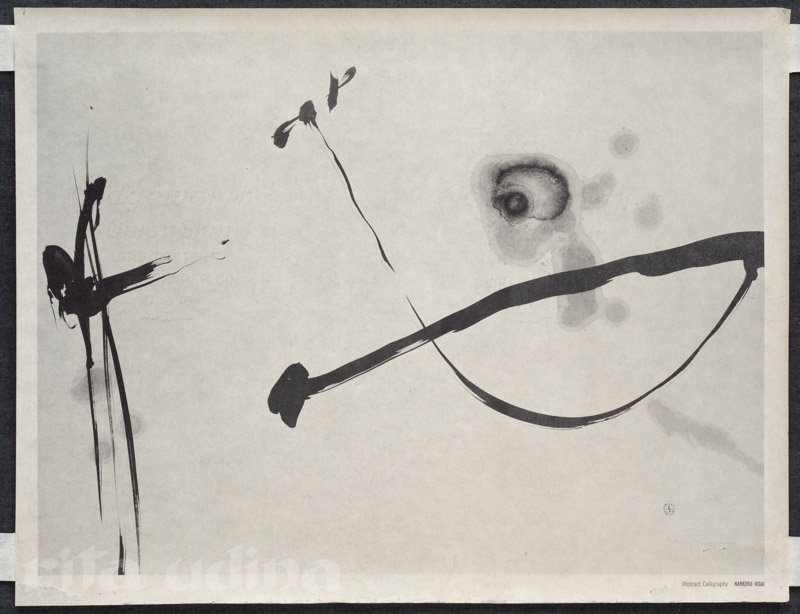

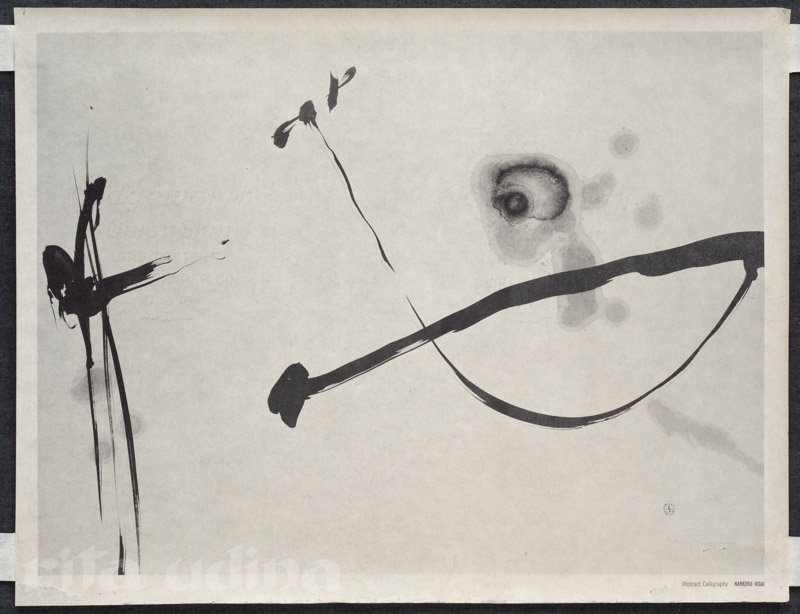

Conservation of an Onion Skin Paper with Abstract Calligraphy by Hidai

The paper that prompted this blog post is a print on onion skin paper from 1968—the reproduction of an abstract calligraphy by Hidai, an artist who in the 1970s shook the age-old Japanese tradition by placing calligraphy at the forefront of the avant-garde. As I mentioned at the beginning, my research is not without personal interest, because the mere fact that the print was produced on this paper already struck me as remarkable. Although it is true that onion skin paper is not ideal for any kind of printing technique due to its extreme thinness, it has indeed been used in specialised art editions. I imagine that in this case it was employed with the intention of mimicking the volatile appearance of Japanese papers.

Onion skin paper before conservation (bottom) and after treatment (top).

It had folds, oxidation, discolouration, cockling, a pressure sensitive tape at the right bottom corner, stains, tears and tattered edges. Paper hinges have been added to mou it on a conservation board for framing purposes.

The finish and appearance of printed onion skin paper are important. Although nearly all the examples shown so far have a rough and cockled finish, onion skin paper did not necessarily have to be this way. In artistic prints, for instance, a smooth finish was preferred, as an uneven surface would otherwise compromise the level of definition required for high quality reproduction.

Regarding the printing technique, and returning to Hidai’s print, the most likely methods that could have been used on this particular paper and in this context would be:

- Mimeograph (stencil duplicating), commonly used for producing low-quality image copies, can be ruled out in this case, as the dot definition is high—unlike the blurred effect typical of the cyclostyle, which works by stencilling ink through a mesh screen. This method was more frequently used internally in schools and businesses rather than for professional publications.

- Letterpress halftone, which would function similarly to a typewriter: an inked, raised metal plate pressed onto the paper. The main challenge with onion skin paper would be its deformation due to pressure and the extended drying time of the ink on such a smooth surface, which could lead to smudging.

- Photographic halftone lithography (offset printing). Offset printing allows for printing on onion skin paper without direct pressure, thus preventing deformation. The varying dot sizes create shading effects, and in this case, they even manage to capture the fine wrinkles of the original paper, as shown in the image below.

Onion skin paper before conservation (bottom) and after treatment (top). Onion skin paper before conservation (below) and after conservation (above). Near the tear—and almost parallel to it—darker lines can be seen replicating the wrinkles of the original paper, which was most likely extremely thin. The reproduction—probably an offset lithograph—achieves its shades and greys through dots of varying diameters. The paper shown in the image, that of the reproduction, shows its own wrinkles, discolouration, adhesive tape, stains, tears, and frayed edges. Paper hinges have been added to mou it on a conservation board for framing purposes.

The conservation treatment consisted in:

- Tape removal with solvent.

- Wet treatment: bathing including chelation (triammonium citrate).

- Deacidification with calcium hydroxide, and at this stage light bleaching was simultaneously held. The lack of lignin in the paper was checked in advance with the florogluciol test (a destructive one, yes).

- Dryed out.

- Reinforcement: Tear mending and losses infilling. Lining at the back with Japanese paper 5 gsm. Starch was used as adhesive for all these steps. Flattening under weight.

- Addition of paper bands to hold the paper on the mat for framing.

The case presented here must have contained a high percentage of cotton fibres—if not entirely—given the effectiveness of the chemical treatment and light bleaching. Such a marked transformation typically requires even greater effort when dealing with lower-quality fibres. The absence of lignin was confirmed by testing a tiny sample taken from the frayed edges with floroglucinol.

In any case, conserving prints is generally less demanding than conserving original drawings… if it weren’t for the fact that we are dealing with onion skin paper, of course! The meticulous work of mending tattered edges and creases, and removing those stubborn adhesive tapes, calls for a great deal of patience. All the more so with wet treatment, which causes the paper to swell significantly before contracting again upon drying.

The restored paper was mounted onto a conservation board using four strips of Japanese paper, allowing it to be framed and enjoyed for many more years.

Footnotes

(1): ROBERTS, Matt T.; ETHERINGTON, Don (1982): Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books. A Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology.

Onion skin

A durable lightweight paper that is thin and usually nearly transparent—so called because of its resemblance to the dry outer skin of an onion. It is used for making duplicate copies of typewritten material, permanent records where low bulk is important, and for airmail correspondence. It is produced entirely from cotton fibers, bleached chemical wood pulps, or combinations of these. The fibers of the paper are long and the paper is sized with rosin, starch or glue; it is usually supercalendered or plated to a high finish, or is given a cockle finish. Basis weights range from 7 to 10 pounds (17 x 22 — 500).

(2): Amherst Libraries, University of Massachussets (checked February 8th, 2025).

Esleeck Manufacturing Company Record (1898-1987). Call no.: MS 505

A manufacturing firm specializing in the production of onion skin paper, the Esleeck Manufacturing Company was established in 1898 as the Monadnock Paper Co. The principal owners, Augustine W. Esleeck and Alfred T. Judd, had worked together with the Valley Paper Mills of Holyoke, Mass., but when striking out on their own, moved to Turners Falls, believing the town to be the ideal location for a mil. Changing their name to Esleeck Manufacturing Co. in 1901, the firm sought to be a good neighbor, using local labor and products from local firms in their manufacturing. After more than 100 years of continuous operation, the company was purchased by Southworth Co. in 2006.

The collection consists chiefly of financial records, but also includes three minute books from 1898-1961 that capture the the company’s early history, as well as a memorial history of the company written by a long-term employee in 1954.

(3): The Catalan invention of the cigarrette blog post by El Gat Saberut (consulted on February 11th, 2025). Very much recommendable!

(4): GUTIÉRREZ-POCH, Miquel (2006). “Tout le monde fume en Espagne”. La producción de papel de fumar en España: un dinamismo singular, 1750-1936. Cap. 16. “Tabaco e Historia Económica. Estudios sobre fiscalidad, consumo y empresa (siglos XVII-XX). Editors: Luis Alonso Álvarez, Lina Gálvez Muñoz & Santiago de Luxán. Published by Fundación Altadis.

(5): Thread by the @CulturalTutor on March the 24th 2023, on X. Very interesting!

(6): AIC Conservation-Wiki (consulted February 8th, 2025).

Original Sizing Agents – Gelatin […]

Contemporary cotton bond paper, onion skin and ledger papers are produced by surface sizing with gelatin or starch and winding into a roll. The roll is left for some time and the moist size is distributed throughout the sheet. The paper is fed through an air drier without tension to yield the strength, hardness and characteristic surface.

(7): WILSON, Helen (2015): A decision framework for the preservation of transparent papers, Journal of the Institute of Conservation. DOI: 10.1080/19455224.2014.999005

(8): UDINA, Rita (2021). Calcos y transparencias, papeles para copiar. Chapt. 2. Papeles en el Balcón. Universidad de Granada. pp. 41-67.

Related blog posts

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Filter post by:

Onion skin paper: History, Uses, Composition and Conservation

Onion skin paper—is it or is it not a tracing paper? This single thought crossed my mind the first time I had to face the conservation treatment of an onion skin paper document. Far from being concerned with nomenclature or classification, I was rather worried about anticipating the setbacks that could arise during the conservation treatment.

Characteristics of onion skin paper

Still today, I dare not make a statement, as there is no clear consensus, but it can be said confidently that onion skin paper is lightweight and translucent… and certainly not made from onion skin! The name comes from its resemblance to the delicate, transparent layers of the vegetable. Admittedly, terminology is open to interpretation and does not always contribute to a better understanding of the topic. In the end, what’s the point of naming and classifying if we do not understand the behavior of the paper, whether for preservation or when applying conservation treatments?

In the latest artefact I was commissioned to conserve, the only certainty was that it was, indeed, onion skin paper—confirmed beyond doubt by the watermark, which stated: “Edgeworth Onion Skin Paper. Rag Content. Valley Paper Co. USA” .

A great opportunity to share what I’ve discovered about onion skin paper and perhaps shed some light on the matter. Or who knows—maybe even spark further insights? Feel free to share your thoughts, as I’m genuinely interested in the topic; all contributions are welcome!

Onion skin paper watermark under transmitted light. Edgeworth Onion Skin. Rag content. Valley Paper Co. EE.UU .

According to general references, it is not only thin and translucent, but a strong and durable paper (1). The indistinct use of the term tracing paper is due to the obvious similarities with it, which enable tracing on onion skin paper as well. In my opinion they both have similar behaviour towards water, that is predictably evil, somehow like a gremlin paper would behave.

History

I wish I had found more precise information on the origin of onion skin paper, which seems to have first been manufactured in the mid-19th century. Progress and specialization in the industry, along with the growing demand for paper for administrative purposes, might have driven its production, which was fully industrial. It was widely marketed between 1920 and 1970. But who knows if there was a specific trigger? Someone who found useful writing on a rolling paper and exploited the idea with variations? …what if that person was a spy called Mata Hari?

Putting imagination aside, one of the oldest producers I’ve found online is Esleeck Manufacturer Co. (1898–1987), specialising in onion skin paper (2). The Amherst Libraries of the University of Massachusetts hold 4.5 linear feet of company records, quietly awaiting someone to unravel their secrets. If Esleeck were not the first to produce it in the USA, I’m convinced that the inventor of their flagship product is mentioned somewhere among their paperwork.

But I have also found examples much closer to home, such as Onion skin Barcino, paper, with some images a few paragraphs ahead Barcino paper takes me back to rolling papers. It turns out that the earliest rolling paper dates from the 19th century (3) and was called Catalan paper, or Barcelona paper (i.e. the Roman Barcino), as it was first produced in Catalonia and exported from there to the Americas (4) . Manufacture of onion skin paper was likely developed by an industry eager to engineer solutions to the demands of the time, driven by a desire to create new products for the market. Perhaps Mata Hari had nothing to do with it, but the link between these two types of paper is not as far-fetched as it might seem. In any case, the dating of onion skin paper in Europe remains unresolved, and I take pride in the fact that paper itself was introduced to the West precisely through the Mediterranean corridor.

Uses and Applications

Its lightness, thinness, transparency, strength, and durability have made it highly valuable for very specific uses.

For instance, it was widely used for copying and duplicating handwritten—but especially typewritten—documents. The paper’s fineness allowed pressure to transfer effectively onto carbon paper, ensuring a precise duplicate on a second sheet of onion skin paper, while its strength prevented the top sheet from tearing under the impact of metal typewriter keys. Up to five copies could be made simultaneously by alternating layers of carbon and onion skin paper, which explains why it needed to be so thin. By the way: did you know that the abbreviation “cc” of emails meaning in copy comes precisely from carbon copy—carbon paper, or copy paper? (5).

The copying process on a typewriter involved placing a sheet of carbon paper (dark blue in the image) between two sheets of onion skin paper. Photo: Richard Polt.

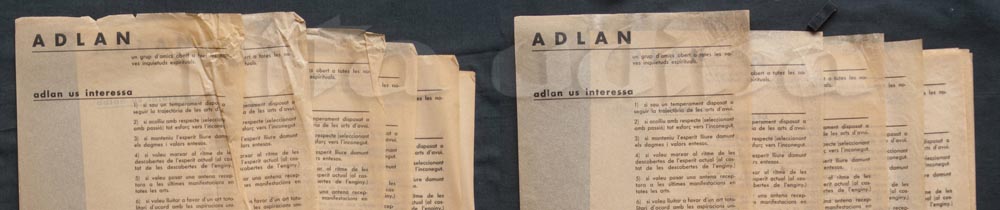

A significant portion of company records from this period were produced on this material. Being lightweight, thin, and durable, it was an ideal material for non-ephemeral archival documentation, helping to save storage space, reduce weight, and minimise future conservation challenges in archival repositories.

Due to its lightness, onion skin paper was also widely used for airmail correspondence—back when mail was a physical material rather than intangible bytes. However, its thinness was not without drawbacks: it could only be written or drawn on one side and was impractical for most printing processes.

“Barcino” onion skin paper for airmail purposes. Photo: Lola Espinosa (oficio-blog.blogspot).

Watermark on Barcino onion skin paper, also for airmail purposes. Photo: watermarks.info

Its transparency has been widely utilised for anything involving tracing, such as technical and architectural drawings. It was also essential in the early process of creating animated films, which even led to the term onionskinning to describe this stage of animation.

Architectural drawing before (left) and after (right) conservation, showing stains caused by the oxidation of the greasy adhesive from those damned pressure-sensitive tapes. Unfortunately, the drawing’s linework overlapped the tape, requiring its removal, cleaning of the adhesive residue, and reapplication using a non-original adhesive.

Project for the Pies Schools by architect Barba Corsini, c. 1960. 1960. Graphite pencil on onion skin paper.

John M. Lounsbery (1911–1976) from the Walt Disney Studios, creating animations over a light table (visible as the circle below). Source: Disney.fandom.

This lightweight, crisp paper, endowed with remarkable mechanical strength, is also ideal for folding into three-dimensional objects—the Japanese art of origami. If ever struggling to flatten an onion skin document, a conservator can always resort to folding it into a paper plane and sending it back to the client with a newfound flying function, should the original one prove beyond recovery!

Origami: Propeller plane made of two pieces of folded onion skin paper by Seiji Nishikawa. Photo: Gilad’s Origami place.

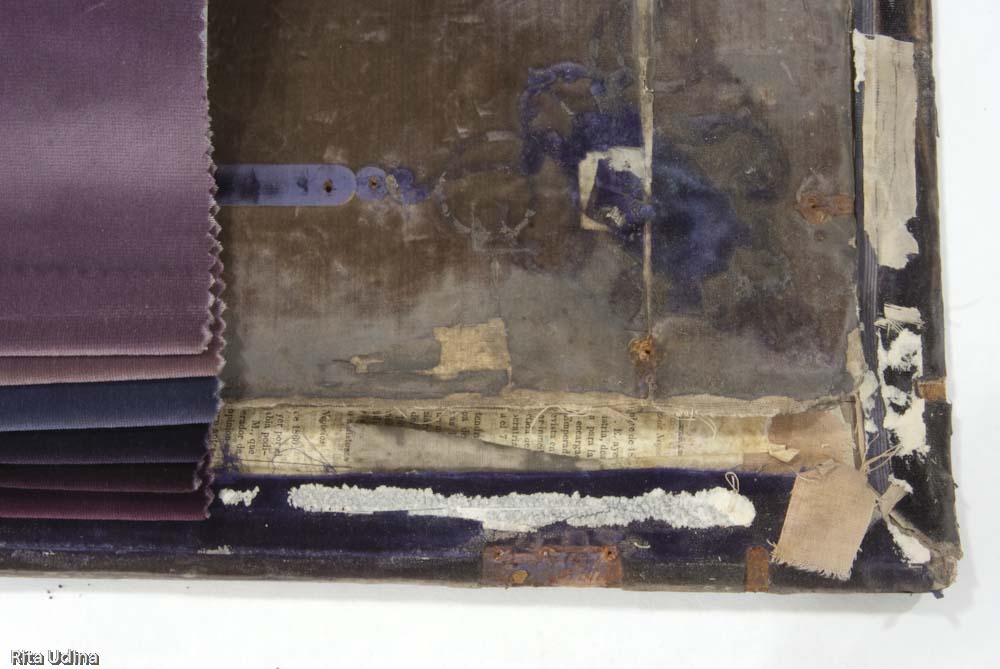

In book publishing, onion skin paper is often used as a protective interleaf for illustrations or prints. Its extreme thinness makes creases almost inevitable, and since it comes into direct contact with oil-based printing inks, it is not uncommon to find it discoloured. Oxidation can also result from adjacent papers of lower quality, further contributing to discolouration.

It is also used as a book dust jacket, particularly in more modern art editions. In these cases, it tends to be more transparent (and glossier) to allow the cover design to remain visible or, at the very least, the title to be legible.

Characteristics

Quality and Composition

There are different qualities of onion skin paper, which, as mentioned, is generally of medium to high quality. The best quality is achieved when the paper pulp is made from rag fibres (cotton or linen). This was indicated by terms such as “rag content,” and if no further details were provided, it meant the paper contained at least 25% cotton fibres (1). If the percentage was higher, it was explicitly stated (e.g., “100% cotton” or the specific proportion). Needless to say, when high-quality fibres are used, the resulting pulp is also more durable and permanent. In lower-grade papers, the remaining pulp would consist of wood fibres which have been chemically treated to remove lignin—which causes poor ageing—and bleached to have a white appearance.

Physical Characteristics

The content of rag fibres is what endows onion skin paper with its remarkable mechanical strength. It allows for typing and heavy folding in origami, for example. This is despite its minimal thickness (ranging between 9 and 35 gsm, approximately), and considering that for the paper to be so thin, intensive calendaring of the paper pulp is required during production. I recently heard a paper miller say that prolonged fibre beating weakens the fibre while strengthening the paper, as defibrillation promotes bonding with neighbouring fibres rather than shortening them. And this is indeed the case, as onion skin paper—at least in my opinion—has greater resistance than many tracing papers, which, despite being thicker, are extremely vulnerable to tearing along the grain. In contrast, onion skin paper tends to be less transparent than most tracing papers. It could be said that onion skin paper is a less advanced version of tracing paper, or its technological predecessor. The fibre compactness is lower, and consequently, it is less transparent and more porous than tracing paper (in general terms).

Sizing and Finishing

Sizings used in onion skin paper production could vary: gelatine, starch (6), rosin or others (1); and the finish could be cockled or smooth. If the paper was left to dry without tension during the final production phase, the surface would become cockled, more porous and slightly wavy. The cockle finish is so called in reference to the wavy surface of the shell. For a smooth finish, additional calendaring during the drying phase—supercalendering(1)—is required. The heat and pressure reduce the voids between fibres, resulting in a more transparent, even glossy. In my opinion, these are harder to distinguish from proper tracing paper, especially if their rag content is minimal or even absent.

The finish largely determines how ink settles on or is absorbed by the paper surface. The more porous the paper, the quicker the ink will be absorbed—meaning the surface dries faster. That’s why all the examples shown here of writing paper, whether for typing or handwriting, have a cockle finish. On the other hand, a very smooth or even glossy surface results in sharper definition of the writing lines or inked areas. If we succeed in preventing such a thin, slow-absorbing paper from warping due to ink moisture or from being accidentally smudged before the ink has dried, then—under these ideal conditions—the ink will spread less along the fibres, resulting in sharper lines. In the example of the dust jacket in the artist’s book, which has a very smooth finish, the paper itself is neither written nor printed on; it is the book cover that carries the text. In the example of the dust jacket in the artist’s book, which has a very smooth finish, the paper itself is neither written nor printed on; it is the book cover that carries the text.

Behaviour and analogies with tracing paper

These physical properties—namely, the fibre length and the compactness between them—largely determine the paper’s behaviour when exposed to water. Onion skin paper expands much more than a “normal” paper (like many tracing papers), and air-drying it often leads to the worst possible outcomes, because as the water evaporates, the paper shrinks uncontrollably, or in a manner we would not prefer.

If we group tracing papers by how their translucency is achieved, we can roughly distinguish three categories(7): In the first type, also called “natural tracing paper”, transparency is achieved mechanically—either through over-beating of the fibres, by applying high pressure during calendaring, or by a combination of both. In the second category, transparency is obtained through chemical treatment of the paper pulp, in which the cellulose undergoes a chemical digestion that transforms it into a colloidal by-product. This chemical treatment is not the same as that used for the delignification of wood pulp mentioned earlier, and consequently, onion skin paper (whether made from wood pulp or rag fibres) could not belong to this group. In the third group, transparency is achieved by impregnating the paper with a coating, (8) usually an oil or wax, which is again quite different from the properties of onion skin paper.

In conclusion, if onion skin paper were to be considered a type of tracing paper, it would fall within the first group, since its transparency is due to mechanical action (calendaring and beating). The main difference between onion skin paper and natural tracing paper lies in the fibre length—in other words, in the less intensive fibre beating during papermaking.

Conservation of an Onion Skin Paper with Abstract Calligraphy by Hidai

The paper that prompted this blog post is a print on onion skin paper from 1968—the reproduction of an abstract calligraphy by Hidai, an artist who in the 1970s shook the age-old Japanese tradition by placing calligraphy at the forefront of the avant-garde. As I mentioned at the beginning, my research is not without personal interest, because the mere fact that the print was produced on this paper already struck me as remarkable. Although it is true that onion skin paper is not ideal for any kind of printing technique due to its extreme thinness, it has indeed been used in specialised art editions. I imagine that in this case it was employed with the intention of mimicking the volatile appearance of Japanese papers.

Onion skin paper before conservation (bottom) and after treatment (top).

It had folds, oxidation, discolouration, cockling, a pressure sensitive tape at the right bottom corner, stains, tears and tattered edges. Paper hinges have been added to mou it on a conservation board for framing purposes.

The finish and appearance of printed onion skin paper are important. Although nearly all the examples shown so far have a rough and cockled finish, onion skin paper did not necessarily have to be this way. In artistic prints, for instance, a smooth finish was preferred, as an uneven surface would otherwise compromise the level of definition required for high quality reproduction.

Regarding the printing technique, and returning to Hidai’s print, the most likely methods that could have been used on this particular paper and in this context would be:

- Mimeograph (stencil duplicating), commonly used for producing low-quality image copies, can be ruled out in this case, as the dot definition is high—unlike the blurred effect typical of the cyclostyle, which works by stencilling ink through a mesh screen. This method was more frequently used internally in schools and businesses rather than for professional publications.

- Letterpress halftone, which would function similarly to a typewriter: an inked, raised metal plate pressed onto the paper. The main challenge with onion skin paper would be its deformation due to pressure and the extended drying time of the ink on such a smooth surface, which could lead to smudging.

- Photographic halftone lithography (offset printing). Offset printing allows for printing on onion skin paper without direct pressure, thus preventing deformation. The varying dot sizes create shading effects, and in this case, they even manage to capture the fine wrinkles of the original paper, as shown in the image below.

Onion skin paper before conservation (bottom) and after treatment (top). Onion skin paper before conservation (below) and after conservation (above). Near the tear—and almost parallel to it—darker lines can be seen replicating the wrinkles of the original paper, which was most likely extremely thin. The reproduction—probably an offset lithograph—achieves its shades and greys through dots of varying diameters. The paper shown in the image, that of the reproduction, shows its own wrinkles, discolouration, adhesive tape, stains, tears, and frayed edges. Paper hinges have been added to mou it on a conservation board for framing purposes.

The conservation treatment consisted in:

- Tape removal with solvent.

- Wet treatment: bathing including chelation (triammonium citrate).

- Deacidification with calcium hydroxide, and at this stage light bleaching was simultaneously held. The lack of lignin in the paper was checked in advance with the florogluciol test (a destructive one, yes).

- Dryed out.

- Reinforcement: Tear mending and losses infilling. Lining at the back with Japanese paper 5 gsm. Starch was used as adhesive for all these steps. Flattening under weight.

- Addition of paper bands to hold the paper on the mat for framing.

The case presented here must have contained a high percentage of cotton fibres—if not entirely—given the effectiveness of the chemical treatment and light bleaching. Such a marked transformation typically requires even greater effort when dealing with lower-quality fibres. The absence of lignin was confirmed by testing a tiny sample taken from the frayed edges with floroglucinol.

In any case, conserving prints is generally less demanding than conserving original drawings… if it weren’t for the fact that we are dealing with onion skin paper, of course! The meticulous work of mending tattered edges and creases, and removing those stubborn adhesive tapes, calls for a great deal of patience. All the more so with wet treatment, which causes the paper to swell significantly before contracting again upon drying.

The restored paper was mounted onto a conservation board using four strips of Japanese paper, allowing it to be framed and enjoyed for many more years.

Footnotes

(1): ROBERTS, Matt T.; ETHERINGTON, Don (1982): Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books. A Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology.

Onion skin

A durable lightweight paper that is thin and usually nearly transparent—so called because of its resemblance to the dry outer skin of an onion. It is used for making duplicate copies of typewritten material, permanent records where low bulk is important, and for airmail correspondence. It is produced entirely from cotton fibers, bleached chemical wood pulps, or combinations of these. The fibers of the paper are long and the paper is sized with rosin, starch or glue; it is usually supercalendered or plated to a high finish, or is given a cockle finish. Basis weights range from 7 to 10 pounds (17 x 22 — 500).

(2): Amherst Libraries, University of Massachussets (checked February 8th, 2025).

Esleeck Manufacturing Company Record (1898-1987). Call no.: MS 505

A manufacturing firm specializing in the production of onion skin paper, the Esleeck Manufacturing Company was established in 1898 as the Monadnock Paper Co. The principal owners, Augustine W. Esleeck and Alfred T. Judd, had worked together with the Valley Paper Mills of Holyoke, Mass., but when striking out on their own, moved to Turners Falls, believing the town to be the ideal location for a mil. Changing their name to Esleeck Manufacturing Co. in 1901, the firm sought to be a good neighbor, using local labor and products from local firms in their manufacturing. After more than 100 years of continuous operation, the company was purchased by Southworth Co. in 2006.

The collection consists chiefly of financial records, but also includes three minute books from 1898-1961 that capture the the company’s early history, as well as a memorial history of the company written by a long-term employee in 1954.

(3): The Catalan invention of the cigarrette blog post by El Gat Saberut (consulted on February 11th, 2025). Very much recommendable!

(4): GUTIÉRREZ-POCH, Miquel (2006). “Tout le monde fume en Espagne”. La producción de papel de fumar en España: un dinamismo singular, 1750-1936. Cap. 16. “Tabaco e Historia Económica. Estudios sobre fiscalidad, consumo y empresa (siglos XVII-XX). Editors: Luis Alonso Álvarez, Lina Gálvez Muñoz & Santiago de Luxán. Published by Fundación Altadis.

(5): Thread by the @CulturalTutor on March the 24th 2023, on X. Very interesting!

(6): AIC Conservation-Wiki (consulted February 8th, 2025).

Original Sizing Agents – Gelatin […]

Contemporary cotton bond paper, onion skin and ledger papers are produced by surface sizing with gelatin or starch and winding into a roll. The roll is left for some time and the moist size is distributed throughout the sheet. The paper is fed through an air drier without tension to yield the strength, hardness and characteristic surface.

(7): WILSON, Helen (2015): A decision framework for the preservation of transparent papers, Journal of the Institute of Conservation. DOI: 10.1080/19455224.2014.999005

(8): UDINA, Rita (2021). Calcos y transparencias, papeles para copiar. Chapt. 2. Papeles en el Balcón. Universidad de Granada. pp. 41-67.

Related blog posts

2 Comments

-

Thank you! Very interesting…I’ m working for 30 years as a paper conservator, but i never heard the term onion paper in Germany….I know the different types of this paper….onion paper sounds very funny 🙂

Best regards Sonja

Thank you! Very interesting…I’ m working for 30 years as a paper conservator, but i never heard the term onion paper in Germany….I know the different types of this paper….onion paper sounds very funny 🙂

Best regards Sonja

Thanks a lot for your feedback, Sonja!

It’s interesting to see that some terms are very popular in some countries and other almost unknown. Here in Spain it’s is super popular among all sort of crafts: dress design, and many others. And as far as I can see very common also in English. But I am aware than in Wikipedia it’s “only” in English, Catalan, Croatian, Azerbazjan and also German! (“florpostt“). I wish I had found who or in which context this term “onion skin” was given.

Warm regards!

rita